Why some brands are betting on long copy to win real attention

In the relentless digital blizzard of 2025, our attention is a currency traded in milliseconds. We are served a daily diet of six-second bumper ads, fleeting social media stories, and what Sushant Sadamate, COO & Co-Founder of Buzzlab, calls "algorithmic junk food." In this cacophony of the immediate, a quiet rebellion is taking place—what Sadamate describes as "a middle finger to the myth that everyone’s brain has shrunk to goldfish size."

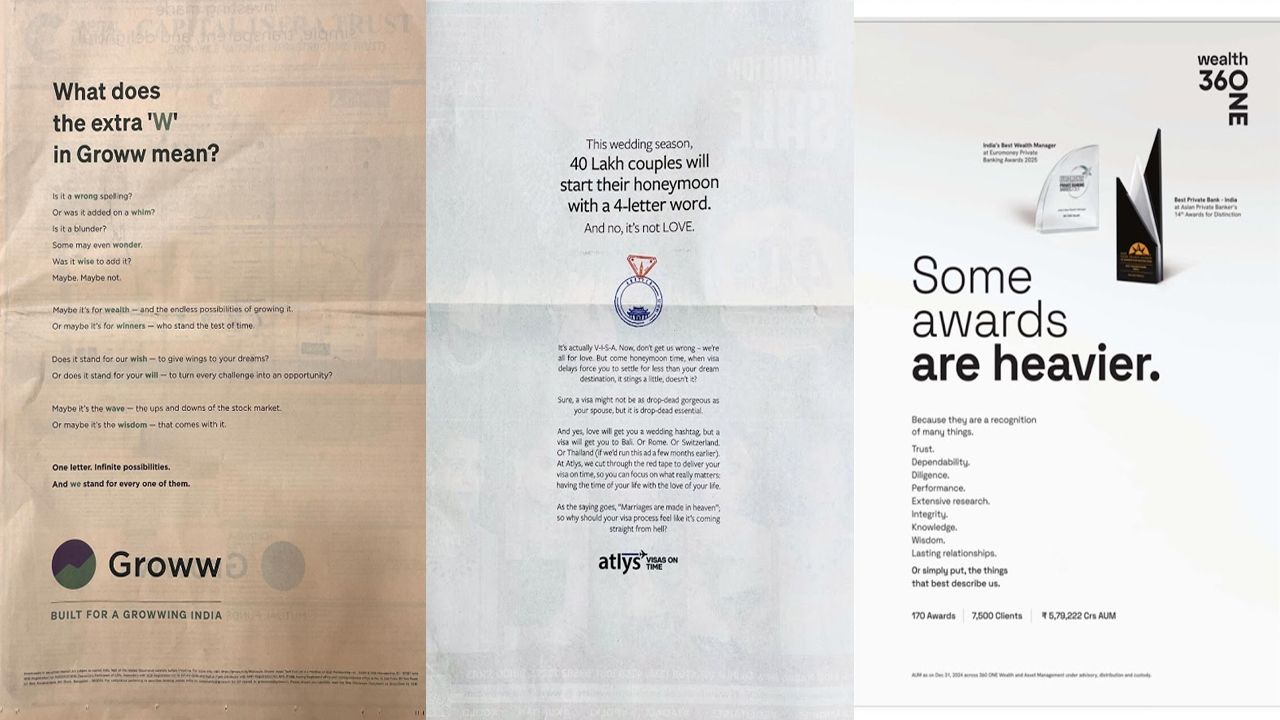

The long-copy print ad, a relic many had consigned to the archives of advertising history, is making a deliberate, and surprisingly potent, comeback.

Or is it? Before we herald a grand return, it's worth challenging the very premise that our collective ability to focus has been irrevocably shattered. As Lakshmipathy Bhat, Advertising & Marketing Communications Leader and SVP at Robosoft Technologies, cautions, "I think we all have to take this assertion that attention spans are shrinking... with a pinch of salt. People still watch or listen to 3-hour podcasts, binge-watch 8 hours of content in a day or two." His point is a powerful reminder that engagement has always been a function of interest, not the ticking of a clock.

This scepticism about a full-blown "return" is a healthy check on industry hype. "I don’t recollect very many memorable ones recently, at least not in the style of 90s and early 2000s advertising," Bhat admits. Nikhil Rangnekar, CEO at Media Circle, echoes this cautious sentiment, stating, “Personally, I don’t see any major shift to long-copy advertising in Print.”

Yet, something is undeniably stirring. In a media landscape defined by what Prachi Narayan, Managing Partner at Havas Play, calls a "culture of acceleration where faster was better, shorter meant smarter, and scrolling became second nature," the deliberate slowness of a well-crafted long-copy ad feels revolutionary. It may not be a tidal wave, but it is a significant current pulling against the tide of digital brevity. It is a quiet insurrection against the noise, a testament to the idea that some messages, some brands, and some stories still need, and deserve, room to breathe.

A rebellion against the dopamine drip

The re-emergence of long-form print isn’t happening in a vacuum. It’s a direct, almost metabolic, response to the environment it finds itself in. As Yuvrraj Agarwaal, Chief Strategy Officer at Laqshya Media Group, puts it, “We’re not witnessing the death of short attention spans—we’re witnessing the rebirth of earned attention.” He argues that this return is a "rebellion... Against the empty calories of content," and that in an age of algorithms, "clarity is radical."

This shift from "attention-grabbing to attention-holding," as Agarwaal terms it, is a response to digital indigestion.

/fit-in/580x348/filters:format(webp)/socialsamosa/media/media_files/2025/06/30/screenshot-2025-06-30-114507-2025-06-30-12-28-10.png)

“The return of long-copy reflects both a reaction to digital fatigue and a renewed appetite for storytelling that goes beyond the scroll,” says Aditi Anand, a Senior Marketing Leader formerly with L’Oréal. She cuts to the heart of the matter with a poignant observation: “I can’t recall a single meaningful story—branded or otherwise-that was told through a 6-second bumper ad or a 300x250 display banner.”

However, Vaibhav Mukim, Creative Director at SW Network, offers a different diagnosis. "I don’t think it’s digital fatigue at all," he argues, telling a story to illustrate his point. "This question reminds me of the story of a guy who would drive really fast everywhere... The problem, however, was that he would arrive where he wanted to and have nothing to do there."

Mukim compares this to the hollow loop of short-form content. "Short-form content leaves you looking for more short-form content," he says. The return to long copy, in his view, is less about fatigue and more because "human beings crave consistency in how they spend their time... a life of constant ups and downs can become wearisome." Long-copy offers a sustained engagement that the frantic pace of digital shorts cannot.

This isn't about an inability to focus, but a discerning refusal to engage with the uninteresting. The legendary Howard Gossage’s words from the Mad Men era, quoted by both M.G. (Ambi) Parameswaran, Founder, Brand-Building.com and Adjunct Faculty - Marketing, SPJIMR and Lakshmipathy Bhat, ring truer than ever: "People don’t read ads. They read what interests them. Sometimes, it’s an ad." Bhat elaborates on this, explaining the shift in a consumer's mindset during moments of high consideration. “If I am in the market to buy a PC, choose a university or buy a DSLR camera, I will pay attention, as long as it takes, if it holds my interest.” In these moments, the consumer isn't looking for a snack; they are hungry for information, nuance, and reassurance.

The answer, then, isn’t a blanket mandate for brevity. Narayan views the trend as a "pendulum swing," a form of "cultural resistance" deeply connected to the broader "slow life" ethos. "From slow fashion to mindful travel to sourdough starters," she explains, "we’ve seen a growing appetite for slowness as an antidote to burnout culture. A long-copy ad in today’s media environment says: you don’t need to rush. You’re invited to think, feel, reflect."

/fit-in/580x348/filters:format(webp)/socialsamosa/media/media_files/2025/06/30/screenshot-2025-06-26-130848-2025-06-30-12-28-56.png)

Sadamate sees it as both “a rebellion and a revelation.” He puts it more bluntly: “The return of long-copy ads is a middle finger to the myth that everyone’s brain has shrunk to goldfish size. What’s really happened is that audiences have become ruthless editors. They skip fluff but crave depth when something actually earns their attention.” In a world screaming for attention, a thoughtful, well-paced conversation can be the most effective way to be heard.

The architecture of trust

Why does a long, text-heavy ad feel so authoritative? In an era rife with misinformation, deepfakes, and AI-generated noise, trust has become the ultimate brand currency. Taking the time and the physical space to build a detailed argument becomes a powerful statement in itself. It signals confidence, thoughtfulness, and, most importantly, respect for the reader's intelligence.

“Long-copy doesn’t just sell—it seduces,” says Agarwaal. “It invites the reader into a conversation, not a clickbait transaction.” He explains that it plays on a powerful psychological lever: commitment bias. "The moment a reader invests time reading, their brain begins justifying the emotional investment. Trust is built word by word, like bricks in a foundation."

“When brands need to shift perception, build credibility, or take a stand, long copy is not optional; it’s essential," asserts Anand. Traditionally, as Bhat notes, long-form is best suited "when there is a story to tell about the product quality, the manufacturing process and the intricacies of what makes it great." He cites classic campaigns like Parker Pen's "Rediscover the lost art of the insult," which used witty, intelligent prose not just to sell a pen, but to sell the very idea of sophisticated communication, creating an entire world of aspiration around the product.

/fit-in/580x348/filters:format(webp)/socialsamosa/media/media_files/2025/06/30/qcbopai90sg71-2025-06-30-12-33-08.jpg)

But where does this credibility truly come from? Mukim suggests it's not the format alone. "Long-copy ads are usually found in magazines and newspapers, which are themselves credible sources of information," he posits. "That said, there is, of course, an added element of credibility... which comes from the fact that to sustain a person’s attention for longer, you need something far more intelligent than getting a person to look for a few seconds."

/fit-in/580x348/filters:format(webp)/socialsamosa/media/media_files/2025/06/30/1732097206285-2025-06-30-12-27-09.jpg)

This is a psychological lever that shorter formats, by their very nature, cannot pull. Sadamate explains that while short-form ads use a "bait and hook method," long-copy "gently leads the reader down a well-thought-out path... where credibility is built layer by layer." It can preemptively answer questions, address doubts, and build an emotional case point by point. This is the heavy lifting required for high-stakes categories like finance, where a brand like 360 ONE Wealth must convey stability and wisdom, or luxury, where a brand like De Beers must weave a narrative of legacy and timeless value.

/fit-in/580x348/filters:format(webp)/socialsamosa/media/media_files/2025/06/30/1743646775725-2025-06-30-12-26-31.jpg)

The human element provides a crucial defence against the rising tide of synthetic media. "As generative content becomes easier and faster to produce," says Narayan, "audiences are already starting to develop a radar for what feels synthetic... A sprawling, emotionally intelligent piece of writing... feels inherently human. And in today’s landscape, that humanness is a competitive advantage." A well-written ad doesn't just transmit information; it creates a connection, inviting the reader into a conversation rather than shouting a slogan at them.

Why print’s canvas seems irreplaceable

While storytelling can exist across platforms, the medium of print offers long copy a unique and increasingly sacred sanctuary. "Print doesn’t just deliver the message, it dignifies it," states Agarwaal. "The weight of the medium adds weight to the message. When something’s printed, it feels permanent. When something’s held, it’s harder to ignore."

Lakshmipathy Bhat explains this using a classic media framework: “Traditionally print, especially newspaper, was seen as a ‘lean-forward’ medium. One tends to read it with intensity and interest, leaning forward.” This active posture of engagement is the polar opposite of the ‘lean-back’ experience of traditional television. Print offers an immersive space. "No pop-ups. No push notifications. Just ink, paper, and persuasion," Yuvrraj Agarwaal adds.

He also identifies a subconscious trigger: cost equals value. "Print is expensive. So, readers subconsciously assume, ‘If they’re spending to say this, it must be important.'"

“Print still offers trust and stature that few digital formats can match,” states Aditi Anand. “A full-page ad in The Times of India or The Hindu feels premium. It’s a statement.” Sushant Sadamate agrees, noting that "Print is not just about content & it's commitment... it slows the readers down, inviting them to take a pause, engage in the matter and immerse themselves fully."

This physicality is irreplaceable. Prachi Narayan’s metaphor brilliantly captures the experiential difference: “Think of it as a vinyl vs. Spotify Shuffle. Vinyl is slow, intentional, and physical.” The experience of vinyl involves the album art, the liner notes, the deliberate act of placing the needle—a ritual that mirrors the immersive qualities of a full-page print ad. It becomes a keepsake, not just a fleeting frame. You can’t swipe it away. You can fold it, save it, leave it on a coffee table for someone else to discover, giving the message a physical persistence and pass-along value that digital metrics can't capture. This tactile experience, as Sadamate points out, "elevates perceived value and authority," making the message feel both literally and figuratively weightier.

However, Vaibhav Mukim offers a pragmatic counterpoint to this romanticism. "I don’t think there is any renewed respect for physical media," he states. "In a world going further and further into the metascape, the lines between physical and digital are constantly fading." He suggests the association of long copy with print is more about tradition than an inherent limitation, a "preconception" that is "bound to change" as we consume more long-form text on screens.

Even so, for now, the physical experience elevates the message. You can’t swipe a full-page ad away. You can fold it, save it, or leave it on a coffee table, giving it a persistence that digital struggles to match.

The endangered craft

With this renewed interest in long copy, a critical and sobering question arises: do we still have the artists to paint on this expansive canvas? The craft of long-form copywriting is a demanding one, requiring the patience of a researcher, the structure of an architect, and the soul of a poet. As Parameswaran, a veteran of print's glory days, warns, “I know how difficult it is to write a long copy ad. It is not as easy as asking ChatGPT.”

“We’re raising a generation of headline hackers when we need narrative architects,” declares Agarwaal. It's a sentiment that cuts to the core of the problem. Bhat offers an even starker assessment: “Are we at risk of losing this craft again? We didn’t have it in the recent past, to lose it.”

This provocative statement underscores a deeper systemic problem, driven by agency economics that prize speed and efficiency over depth. “The industry has spent years optimising for brevity," laments Narayan, training writers to think in "punchlines and punch-ins, not paragraphs and pace." Bhat adds crucial context, noting that it's wrong to pit long against short-form, as both are difficult disciplines. "Writing a short, snappy headline is very hard," he says, but "long form copy is perhaps even harder as one has to build an argument, create a structure, hold audience attention and drive home the point."

The craft itself is immensely demanding. Agarwaal breaks it down beautifully: "The craft of long-copy requires: Pacing like a novelist, Logic like a lawyer, Emotion like a poet." Yet, as he notes, "today’s young writers are trained on A/B test subject lines, not storytelling arcs." This focus on short-term metrics is driven by economics.

The reasons are also economic. Mukim points out that the industry is "huge and non-uniform... but, by and large... is controlled by people who want a safe return on their investment. Which is why it is slow to change and accept new paradigms." This risk-averse culture often defaults to the perceived safety of short, measurable, digital-friendly formats.

The core issue may be a crisis of mentorship and inspiration. "The new crop of copywriters might not have heroes to look up to when it comes to top-notch copywriting in English, especially long form," Bhat reflects. The names that once inspired—Ogilvy, Bernbach, Gossage—feel like distant historical figures.

Are we doing enough to reverse this decline? "Not really," Anand states bluntly. To revive the art, the industry must make a conscious choice to value it again. This means giving writers the most precious resource: time. Time to think, to research, to write, to fail, and to rewrite. It means creating a culture where a beautifully crafted paragraph is celebrated as much as a viral meme.

"Considering that our industry is currently surrounded by a whirling vortex of auto-generated blurbs and AI-assisted copy," says Narayan, "the true differentiator won’t be speed. It’ll be soul. And long-form writing, when done right, is all soul."

"What the industry needs is mentorship over metrics, and craft over click-throughs," Agarwaal insists.

If this resurgence is to be more than a fleeting moment of nostalgia, the industry must heed this call. For as Sushant Sadamate warns, if we allow this craft to perish again, "we won't just lose good copy, we’ll lose brands' ability to genuinely connect." And in the end, in a world saturated with noise, that deep, human connection is the only thing that ever truly mattered.

News