Ancient Indian Textiles That Outlived Fast Fashion by 2000 Years

Before “eco-conscious clothing” became a buzzword, before runways started boasting about sustainability, India was already weaving masterpieces that were slow, ethical, and rooted in the land. For centuries, communities across the subcontinent have crafted textiles not in factories but in courtyards, under neem trees, beside riverbanks — with skills passed down through generations, not downloaded from design schools.

These were not just fabrics. They were stories dyed with natural pigments, shaped by regional identities, and touched by hands that understood patience. From airy muslin that once dressed emperors to Ajrakh prints soaked in desert tradition, these textiles weren’t chasing trends. They defined tradition.

Today, in a world drowning in disposable fashion, these age-old techniques stand tall — timeless, relevant, and beautifully resistant to fading away. Here’s a look at five such textiles that continue to beat fast fashion at its own game.

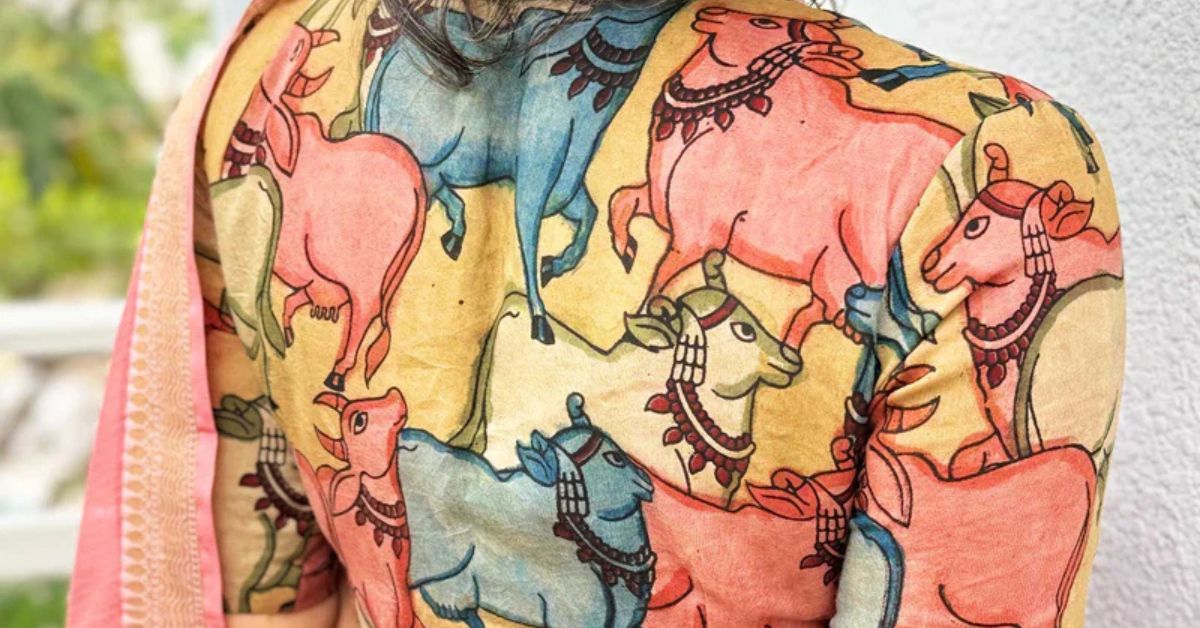

1. Kalamkari – Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

Kalamkari dates back over 3,000 years, with roots in the temple towns of Machilipatnam and Srikalahasti.

Kalamkari dates back over 3,000 years.

Kalamkari dates back over 3,000 years.

How it was used

Initially, it was a sacred art form used to create temple hangings, scrolls, and story panels. Artisans narrated episodes from epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata through hand-drawn motifs.

How it was made

The word comes from kalam (pen) and kari (craftspersonship). Artisans used bamboo pens and natural dyes from plants like indigo, myrobalan, and pomegranate peels. It’s a 23-step process involving repeated washing, dyeing, and drying.

Modern day blends

Kalamkari has made its way into urban wardrobes as block-printed kurtas, dupattas, sarees, and even home furnishings. The designs may be trendier now, but the process remains rooted in age-old wisdom.

Sustainability: Kalamkari is dyed with natural, plant-based pigments and follows a water-efficient process with minimal machinery. It’s handmade, non-toxic production supports rural artisans and eco-conscious fashion practices.

2. Ajrakh – Gujarat and Sindh (Now in Pakistan)

Believed to have originated over 4,000 years ago in the Indus Valley Civilization, Ajrakh continues to thrive in Kutch and Sindh.

Ajrakh now features on sarees, stoles, shirts, and bedsheets. Picture source: Wandering Silk

Ajrakh now features on sarees, stoles, shirts, and bedsheets. Picture source: Wandering Silk

How it was used

Traditionally worn by pastoral communities and Sufi mystics, Ajrakh was both symbolic and practical. The thick cotton protected from harsh sun and dust.

How it was made

Made using natural dyes like indigo, madder, and jaggery, Ajrakh involves up to 16 steps of resist-dyeing and block printing. Craftsmen use intricately carved wooden blocks to layer symmetrical geometric patterns.

How it’s used now

Ajrakh now features on sarees, stoles, shirts, and bedsheets. Designers are blending it with modern silhouettes while keeping the eco-friendly essence intact.

Sustainability: Ajrakh uses natural dyes and sun-bleaching, eliminating harmful chemicals and energy use. It supports rural artisan communities, preserving traditional ecological knowledge.

3. Muslin – Bengal (Now Bangladesh and Bengal)

Muslin, especially Dhaka Muslin, was at its peak during the Mughal period (16th–18th century), though references date back to the sixth century BCE.

Muslin is made from organic cotton, hand-spun and woven with minimal energy use. Picture source: Wikipedia

Muslin is made from organic cotton, hand-spun and woven with minimal energy use. Picture source: Wikipedia

How it was used

Called “woven wind,” Muslin was so fine it was once mistaken for mist. Royals in India and Europe draped it in multiple folds, yet it remained light and breathable.

How it was made

Made from Phuti karpas, a rare cotton variety that grew along the banks of the Meghna River, Muslin was spun and woven entirely by hand. It could take six months to a year to complete one piece.

How it’s used now

Though the original art nearly vanished under colonial rule, Muslin has seen a revival. It’s now woven in pockets of Bengal and Bangladesh, mostly for sarees, scarves, and luxury apparel.

Sustainability: Muslin is made from organic cotton, hand-spun and woven with minimal energy use. The ultra-fine texture requires no heavy processing or machinery, supporting eco-friendly craft revival and local economies.

4. Chikankari – Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

Chikankari is an embroidery believed to have been introduced by Nur Jahan, Mughal Empress and wife of Jahangir, in the 17th century.

Chikankari was used for royal robes, kurtas, and veils. Picture source: Wikipedia

Chikankari was used for royal robes, kurtas, and veils. Picture source: Wikipedia

How it was used

Originally done on muslin, Chikankari was used for royal robes, kurtas, and veils. It symbolised elegance — subtle, intricate, and regal.

How it was made

Chikankari involves over 30 types of stitches like phanda, murri, and bakhiya, all done by hand. Artisans often draw the design in washable ink and embroider over it using white thread on soft fabric.

How it’s used now

It remains a popular summer staple. Chikan kurtas, dupattas, and sarees are now worn by everyone from students to CEOs — proof that delicate can still be durable.

Sustainability: Chikankari promotes slow fashion through its unique hand embroidery on breathable, natural fabrics like cotton and muslin. It empowers women artisans and reduces carbon footprint through low-impact processes.

5. Patan Patola – Gujarat

Patan Patola originated in the 11th century in Patan, Gujarat, where Salvi weavers moved from Maharashtra with royal patronage.

Patan Patola sarees were worn by queens and aristocrats. Picture source: Pinterest

Patan Patola sarees were worn by queens and aristocrats. Picture source: Pinterest

How it was used

Once considered a symbol of wealth and status, Patan Patola sarees were worn by queens and aristocrats. They were also traded as diplomatic gifts.

How it was made

Patola is a double ikat — both warp and weft threads are tie-dyed separately before weaving. It can take six months to a year to complete just one saree. The colours don’t fade, and the design appears identical on both sides.

How it’s used now

Today, Patola sarees are luxury collectables. Though expensive, they’re a once-in-a-lifetime buy, valued for their symmetry, technique, and cultural pride.

Sustainability: Patola sarees are made with natural dyes and handwoven on traditional looms. The intricate, time-intensive process supports craft longevity, slow fashion, and zero-waste artistry passed down for generations.

Wearing legacies through these textiles

In a world rushing to buy what’s trending, these traditions slow us down — in the best way possible. Each piece is not just stitched or dyed; it’s nurtured, passed down, and made with a sense of responsibility. These textiles weren’t meant to be thrown away after one use. They were designed to live, breathe, and last.

And maybe, that’s the real definition of fashion: not just what we wear, but how we choose to honour the hands that make it.

News