Why This Filmmaker Couple Gave Up Luxe London Life to Build A Mud & Bamboo Mountain Retreat In Himachal

Tucked away in the mountains of Dharamshala, where mobile networks waver and concrete retreats give way to pine forests and terraced fields, sits a homestay unlike most others; not simply for what it offers guests, but for what it refuses to compromise on.

Kosen Rufu Village Recluse is not the kind of place you stumble upon. To reach it, you have to leave your car behind and walk a stretch of narrow path that cuts through the slopes of Thathri village. There are no neon boards or manicured driveways here, only a cluster of mud and slate cottages rising gently from the earth, as though they’ve always belonged.

But this isn’t a place frozen in tradition. It’s a retreat shaped with intention, a quiet rebellion against the pace and practices of mainstream tourism. Built almost entirely from handmade bricks, bamboo, and slate, Kosen Rufu is the result of years of labour, a deep personal calling, and the guidance of one of India’s most revered eco-architects, Delia Kinzinger — known to many as Didi Contractor.

Raman Siddhartha and Manju relocated from London to Dharamshala to build a sustainable homestay.

Raman Siddhartha and Manju relocated from London to Dharamshala to build a sustainable homestay.

Building in the lap of nature

The homestay, as it stands today, began as a piece of difficult terrain. It was constructed on a patch of land in Thathri, off Khanyara Road in Dharamshala, bought in 2018 by filmmaker Raman Siddhartha. The idea, he says, was never about just building a stay.

“I’ve lived in London for 25 years, but I was born in Himachal. My father, a bureaucrat, took me to remote villages all the time. I grew up seeing ‘kachcha makaan’ (mud homes) that were deeply rooted in the land and community,” Raman says. “That never left me. It stayed in my subconscious that if I ever returned, I would build a mud house.”

Returning to India with his wife and creative partner Manju Narayan in 2016, the couple initially explored the region as filmmakers. But the growing clutter of concrete homes, even in remote Himalayan corners, deeply unsettled them.

“Everyone was in a rush to ‘develop’,” Manju says. “Concrete everywhere. It felt like we were losing the soul of the land.”

The couple’s decision to build an entirely sustainable home and eventually, a homestay, began as a personal project. But soon, the scale and significance of what they were creating outgrew that scope.

Didi Contractor’s architecture of resistance

To bring their vision to life, Raman and Manju reached out to Delia Kinzinger, the German-American architect better known in the region as Didi Contractor. Based in Dharamshala, Kinzinger had already spent decades building eco-sensitive homes that honoured local traditions and terrain.

She was, by all accounts, uncompromising. “She refused to use AutoCAD,” Raman says. “Every sketch was hand-drawn. Every angle was measured by instinct and wisdom.”

The late architect had her doubts initially. But the project’s intention, sincerity, and the couple’s desire to reconnect to their roots eventually won her over. Her involvement changed everything.

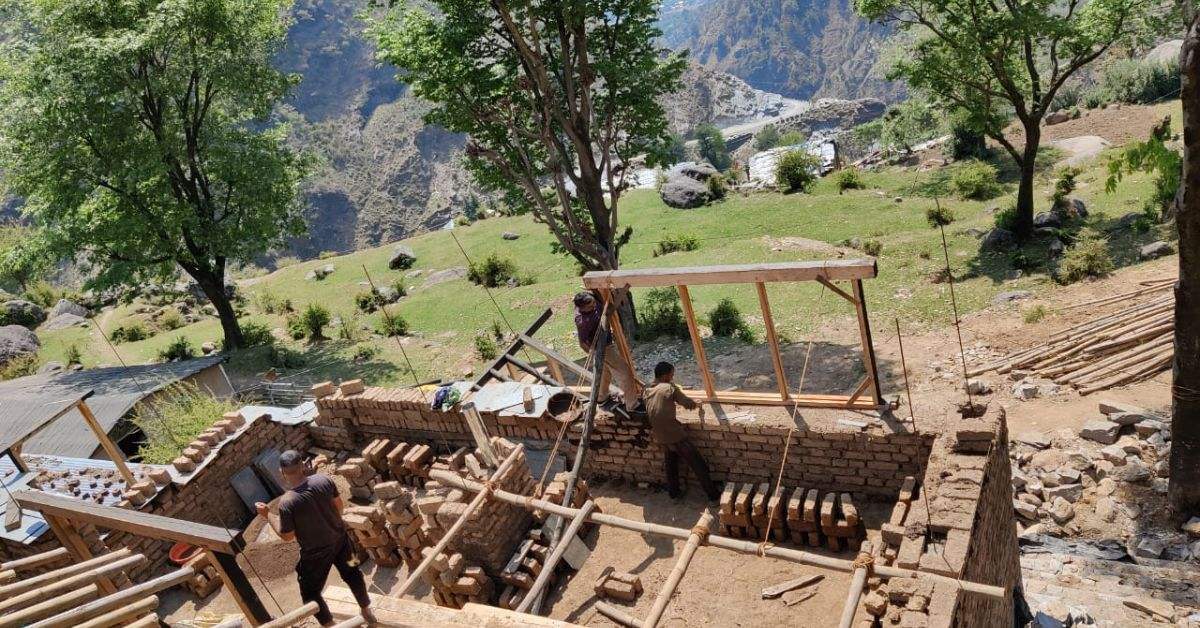

The structures at Kosen Rufu were designed using mud bricks made from earth sourced locally, dried and shaped by hand. “Drying them was a challenge,” Raman admits. “The mountain weather is unpredictable. Many bricks were washed away by sudden rain.”

A long walk to sustainability

Despite setbacks, they never resorted to cement. The foundation used bamboo, walls were packed with stone and mud, and even the roofing slate was locally quarried. No industrial material was brought in. The design incorporated 18-inch thick walls, natural insulation using pine needles and dust, and multi-layered mud coatings that mimicked the strength of concrete — without the environmental cost.

The design incorporated 18-inch thick walls, natural insulation using pine needles and dust.

The design incorporated 18-inch thick walls, natural insulation using pine needles and dust.

The construction for this homestay began in 2019 and spanned nearly four years. With no road access at the time, every material, from bricks to bedding, had to be transported by mules. “Friends and family called us mad,” Raman laughs. “They said this was a foolish thing to do. But we were clear, we didn’t want to disturb the land.”

In fact, the path to the retreat remains intentionally non-motorable. Cars stop some distance away; the rest must be walked. “This was Didi ma’am’s principle,” he says. “The home should adapt to the land, not the other way around.”

Today, a small road exists, thanks in part to the couple’s efforts with local authorities. And the road is primarily not for tourists, but to help the villagers in nearby homes access emergency care more easily.

From hostility to harmony

At first, not everyone in Thathri was convinced. “People filed complaints against us,” Manju recalls. “They couldn’t understand why anyone would build a mud house willingly; it was seen as something the poor do out of necessity.”

Every beam, every brick at Kosen Rufu Village Recluse holds a story, not just of resistance to mainstream tourism, but of radical care for the land. One person who oversaw this careful dance between terrain and technique was the chief architect Naresh Sharma, who worked closely with both the founders and Delia Kinzinger to bring the retreat to life.

No industrial material was used during the building of this sustainable home stay.

No industrial material was used during the building of this sustainable home stay.

“This wasn’t a copy-paste project,” Naresh says. “In the mountains, you can’t force your ideas on the land. You have to read the slope, feel the weather, and understand how wind moves through the valley. Only then can you build something that lasts, not just physically, but spiritually too.”

But time and tea heal most things. As the couple integrated with village life, attending weddings, sharing meals, and participating in festivals, their intentions became clearer. “Now, we’re seen as part of the community,” Manju says. “And more importantly, the locals are starting to see value in their traditional homes again.”

That, perhaps, is the most lasting impact of Kosen Rufu; it doesn’t just welcome visitors, it encourages local preservation. The couple now advises villagers not to tear down their ancestral homes and is considering hosting community workshops on sustainable construction.

A stay that teaches you to slow down

The retreat’s name, ‘Kosen Rufu’, is a Japanese phrase meaning ‘peace and happiness’ — a reflection of the couple’s Buddhist practice. True to its name, the homestay offers little by way of luxury as conventionally defined. There are no TVs, no air conditioning, and often, no mobile signal.

Instead, guests find mud cottages warmed by the sun, the scent of pine wood, and views that stretch beyond the folds of the mountains. “We had no scaffolding like you’d see in cities. Most of the work was done by local artisans using traditional tools. It was a collective memory — something modern design has almost forgotten,” Naresh mentions.

“People come here and at first, they’re unsettled by the quiet,” says Manju. “But by the end, they don’t want to leave.”

A weekend getaway at Kosen Rufu will recharge your soul.

A weekend getaway at Kosen Rufu will recharge your soul.

Rooms and huts start at ₹3,000 per night, with varying tariffs depending on accommodation type. Each space is equipped with chemical-free bedding, eco-friendly toiletries, and locally-made linens. Plastic is banned on the premises.

Even the water tanks are made from double-insulated steel, avoiding plastic and helping regulate water temperature, which is critical during winter months when freezing is a risk.

But beyond materials and methods, the retreat’s hospitality stands out. “We’ve trained our staff to offer tea and water to anyone who walks in, even if they’re not guests,” says Manju. “It’s about creating a space that feels like home.” Local women and youth are employed as caretakers and guides, creating livelihood opportunities in the region while preserving cultural ties.

“Staying here was a refresher from the crazy city life. My family loved every bit of it. And the food is really delicious and fresh here,” says Aditya Kumar, a software developer who visited the property with his family.

The recluse has also found its place in the heart of celebrated actor and poet Piyush Mishra. “During one of his recent visits to Kosen Rufu, Mishra shared his happiness, attributing to the peace and quiet the stay gave him in contrast to the ignorant and egoistic world he’s come from,” Raman mentions.

Celebrated actor and lyricist Piyush Mishra was all praise about Kosen Rufu.

Celebrated actor and lyricist Piyush Mishra was all praise about Kosen Rufu.

What sustainability costs and saves

Building a retreat of this kind wasn’t cheap. “We went nearly 30% over budget from our planned ₹2–2.5 crore,” Raman says. “But we never considered cutting corners.” And yet, the investment has paid off, not just in guest satisfaction, but in minimal maintenance.

Thanks to Didi Contractor’s construction techniques, the mud walls are resilient through the seasons. The natural plasters used, involving pine needles and multiple binding layers, have kept out seepage and cracks. “We haven’t had to spend on repairs the way you would with concrete homes,” Raman explains.

The real saving, though, lies in preserving the terrain. By not flattening land or using heavy equipment, the retreat has avoided the kind of erosion and drainage issues that plague many mountain resorts.

Looking ahead and expanding with caution

As interest in the homestay grows, the couple is considering adding a few more mud cottages to the compound. But expansion will be slow and in line with the core philosophy.

“We’re not here to scale like a chain,” Raman says. “The idea is to deepen, not widen.”

What they do hope to grow is community engagement by helping more people understand that sustainability isn’t about aesthetics, but ethics. “It’s not just how you build,” Manju adds. “It’s how you live.”

Each and every corner of Kosen Rufu is crafted with the aim of preserving the environment.

Each and every corner of Kosen Rufu is crafted with the aim of preserving the environment.

Kosen Rufu Village Recluse is not a prototype for mass tourism, and perhaps that is its greatest strength. It refuses replication. It asks instead for a reflection of what it means to belong to a place, to build with respect, and to host with humility.

The retreat is not just about living closer to nature, but about learning how to live without harming it. It doesn’t lecture, it invites.

As Manju Narayan puts it: “We’re not just offering a bed and a view. We’re asking people to experience the value of the land, the culture, and the pace of life we’ve forgotten.”

For those who arrive with hurried feet and cluttered minds, the quiet of Kosen Rufu doesn’t fill a void, but it reminds you it was never meant to be filled with noise. In a world fast losing its grounding, this little homestay on the slope of Thathri holds its ground not by standing tall, but by sinking its roots deeper into the soil.

News