Death of single screen theatres and a viewing culture

It’s August 1994, raining cats and dogs. As people rush home to avoid the floods, Tilak cinema in the small town of Dombivli in Maharashtra is overflowing with Bollywood buffs, swaying to the tunes of ‘Didi Tera Dewar Deewana’ from the blockbuster ‘Hum Aapke Hain Koun..!’ They don’t mind if the show is houseful and they have to sit on wooden benches in front of the actual seat. They don’t mind the water seeping into the theater because of the rain. Tonight, the theatre isn’t just a shelter from the storm: it is a celebration, a community, a kind of magic only single screens could create.

For decades, single screen cinemas were the most popular form of entertainment in India. With tickets priced for the masses, they welcomed families under one roof. In households with a sole breadwinner, single screen theatres made collective joy affordable. Joy, back then, was not restricted to an individual: it was loud, messy and shared. People laughed together, cried together, and clapped in sync with strangers who felt like cousins by the time the credits rolled. A Sunday outing at the local theatre was not only about the movie but was also about the shared rickshaw ride, the street-side snacks and the post-movie debate over who acted better. These screens were not just physical structures: they were avenues for emotional connection. Families became audiences, and audiences felt like families.

But now, the world outside the single-screen theatre has changed. Somewhere along the way, the family outing became a personal plan. As standard of living increased, our sense of joy became more private, more compartmentalised. The warmth of sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in a darkened hall gave way to watching movies on-demand, on a phone, alone, with noise-cancelling headphones. Pankaj Jaisinh, former CEO of Distribution at UFO Movies, observes, “Earlier, one earning member bore the cost for the whole family. Today, everyone earns and wants to spend on themselves. Ticket prices overall have gone up too, so people think, ‘Why should I pay for four when I’m only interested in watching it myself?’” The logic is simple but telling: entertainment, once collective by nature, has turned into a private experience. With OTT platforms and multiplexes offering tailor-made comfort, watching a film became less about community and family time and more about convenience and personalisation. As priorities shifted from togetherness to self-care, single screens were left behind, not just as theatres, but as ideas.

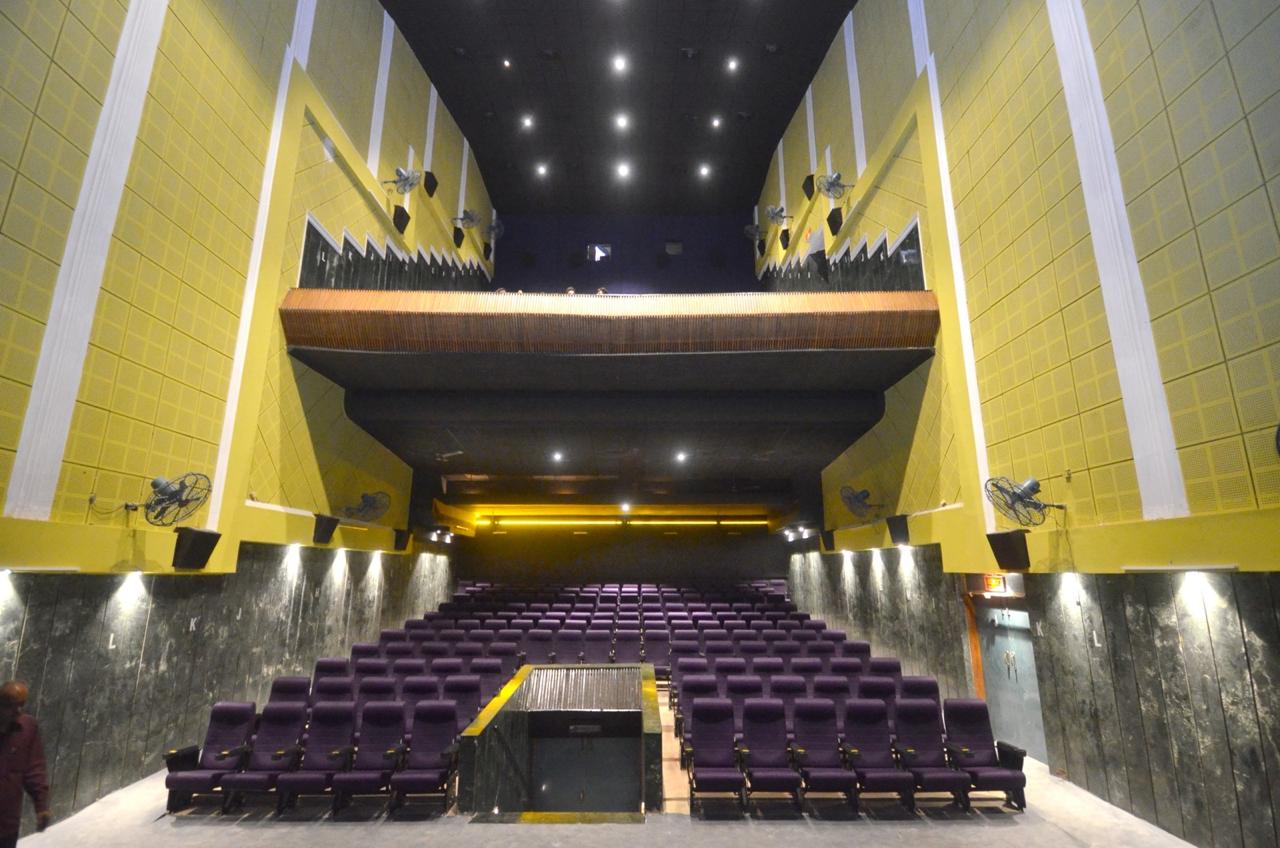

Tilak Talkies at Dombivli in Thane. The stall and balcony concept still in play.

Tilak Talkies at Dombivli in Thane. The stall and balcony concept still in play.

At the same time, many single screen cinemas did little to change with the times. While the world outside upgraded, single screen cinemas stood frozen in time, perhaps thinking that what worked 20 years back will work today as well. “We still have people who come for Rajinikanth films like it’s a festival; they perform poojas, decorate the place,” says Mahendra Vira, owner of Tilak Talkies in Dombivli.

“Most single-screen theatres today suffer from poor maintenance, unclean premises, crumbling interiors, lack of air-conditioning, and unhygienic washrooms. Unlike multiplexes that offer ample parking, clean lobbies, and ambient lighting, most single screens are tucked into older, crowded city centers where space is a constraint and infrastructure is decades old,” remarks Arvind Chaphalkar, owner of City Pride Multiplex of Pune, one of India’s first multiplexes. The absence of comfort and luxury — things modern audiences increasingly seek, pushes people away. Cinema, once a communal escape, now feels like a compromise in these halls. It’s no surprise, then, that over 20,000 single-screen theatres have shut down in India over the last three decades, leaving just around 5,500 struggling to survive. Nostalgia can fill a few seats, but not enough to keep the lights on.

This is where multiplexes and other forms of digital entertainment platforms benefitted. They understood the modern viewer’s need for control, comfort, and customisation. Recliner seats, gourmet snacks, air-conditioned lobbies, and now, algorithms that know what you want to watch before you do. The audience, once happy with wooden benches and community chatter, now seeks silence, space and seamlessness. In contrast, single screens offer little more than the movie itself. What used to be a night out with the family has turned into a solo scroll through streaming platforms. The decline of single screens, then, is not just about outdated infrastructure, but also about how entertainment itself has become a solitary habit, dressed up as luxury.

What we are watching slip away with single-screen cinemas is not just an old way of watching movies, it is an old way of being together. A time when joy was noisy and shared, when families sat side by side without needing to speak, and love was shown in the simplest way — by showing up. Today, the halls are quiet, the projectors dim and the magic that once brought people under one roof flickers faintly, if at all. We may have moved on to sharper screens and cleaner lobbies, but somewhere in the silence, we have lost the feeling of collective wonder. The seats are empty now, but maybe the real vacancy is elsewhere.

— The article was co-authored by Dr Ninad Patwardhan and Prof Manjula Srinivas from FLAME University, Pune

Arts