60 years of NSD Repertory: The learning stage

Back in September 2024, I found myself walking once again through the corridors of the National School of Drama. The air was electric. Buntings fluttered, old photographs were being dusted off and pinned to the walls. There was a celebratory atmosphere, as the Repertory Company was turning 60 — and the space pulsed with something more than nostalgia. It was alive.

In a country where theatre speaks in a thousand tongues and tradition and modernity move unevenly across its cultural landscapes, the notion of a singular ‘national theatre’ is, at best, a contradiction. And yet, for 60 years, the NSD Repertory Company has carved out a space that defies singularity. A cauldron of experimentation, rigour and artistic inquiry, it has endured, not as a monument, but as a living organism.

Since its inception in 1964, the Repertory was never meant to be a museum of mothballed classics. It was — and remains — a laboratory. A space of analysis, risk, failure and creative combustion. A space where artistes ask — What does form mean? Who is the audience? Why this play, now? Six decades later, while silently gazing at the photograph gallery, I wondered if these questions still haunt the actors and the institution.

The spirit that birthed this institution traces back to Ebrahim Alkazi — visionary, taskmaster, modernist. Under his stewardship, the Repertory began with just four actors: Ramamurthy, Meena Williams, Sudha Shivpuri and Om Shivpuri. It was conceived as a launchpad for NSD graduates to take their three years of intense training beyond the classroom — into the risky terrain of professional theatre. Initially, the Repertory was an adjunct to the school, but slowly, as the Repertory grew, it became an independent company, with its own infrastructure, identity and a director at the helm.

The Repertory would go on to become one of Indian theatre’s most important staging grounds. Over 120 productions. More than 70 playwrights. Some 50 directors. Its performance spaces have reverberated with voices of playwrights as varied as Bhasa and Brecht, Lorca and Elkunchwar. The plays performed have been as wide-ranging. From ‘Look Back in Anger’ to ‘Ghasiram Kotwal’, from ‘Andha Yug’ to ‘Begum Ka Takiya’, the Repertory has staged the contradictions of a complex nation.

Plays like ‘Mukhyamantri’, a biting political satire, forced Delhi to confront uncomfortable truths. Its crisp realism lit a fire amid an apathetic middle class. ‘Begum Ka Takiya’, in contrast, offered a gentle, Sufi-tinged poeticism. It was a story about faith, belonging, and the invisible histories of Muslim India. Both were directed by the maverick director Ranjit Kapoor.

And then there was the firebrand spirit of Satyadev Dubey, whose production with the Repertory on Mahesh Elkunchwar’s ‘Virasat’ refused to offer comfort. It agitated, fractured, unsettled. Dubey’s presence loomed — always pushing the envelope, never letting the Repertory rest on its pedigree.

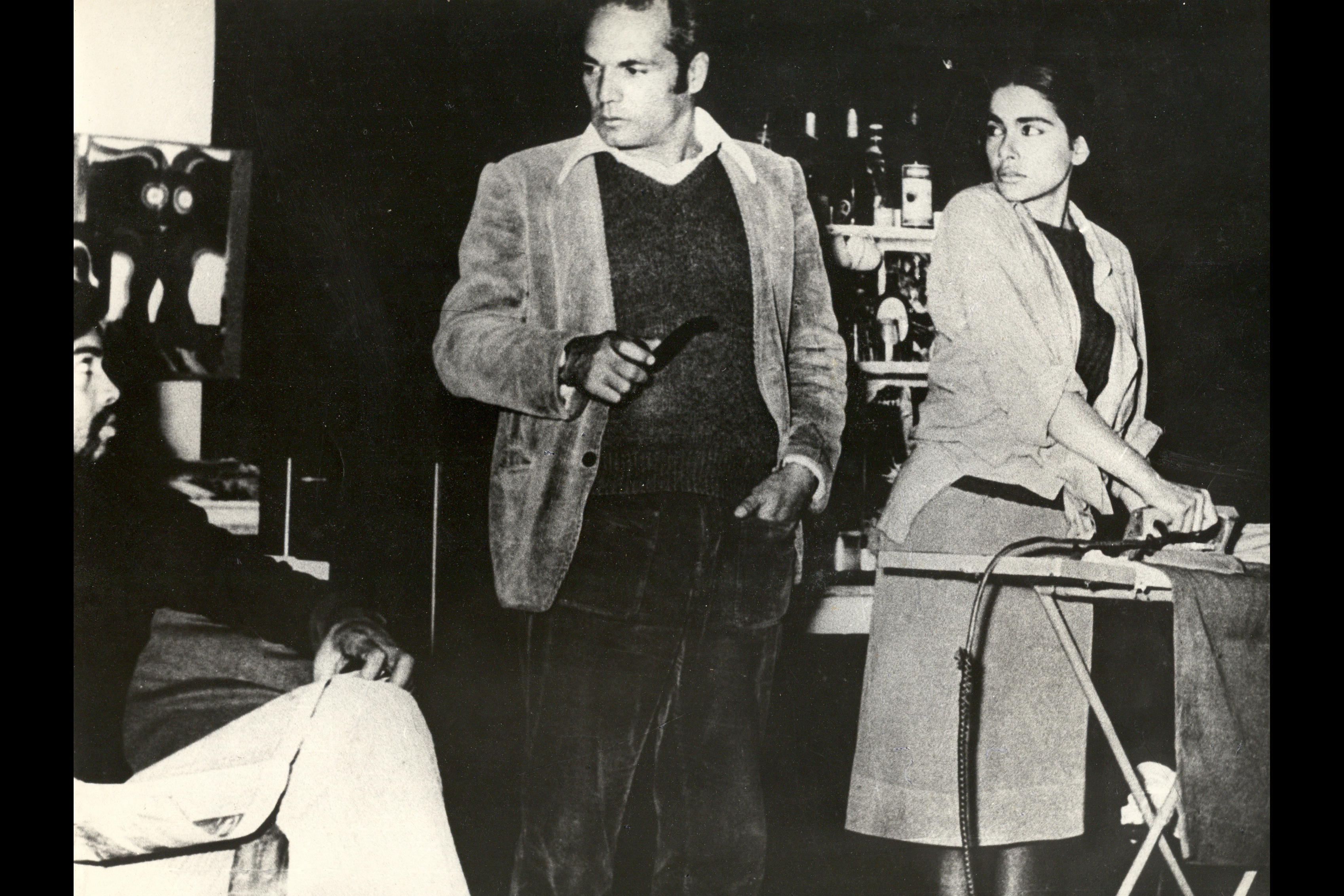

‘Look Back in Anger’, Ebrahim Alkazi’s landmark production of John Osborne’s modern classic.

‘Look Back in Anger’, Ebrahim Alkazi’s landmark production of John Osborne’s modern classic.

And as I walked through those memory-soaked corridors, I paused before a photograph of ‘Look Back in Anger’, Alkazi’s landmark production of John Osborne’s modern classic. I remember sneaking into late-night rehearsals under the great banyan tree at Meghdoot Theatre, where the stalwarts of the Repertory were practising their craft through voice exercises and character analysis. I was a first-year student then, awestruck and clueless, knowing abstractly that we were in the presence of something seismic.

That play clung to me: Manohar Singh as Jimmy Porter, raging with elegant violence; Uttara Baokar, as Helena, turned an ironing press into a weapon — her sarcasm dripping like acid; Surekha Sikri, brittle and devastating as Alison — her silences louder than any line. Delhi audiences queued up for hours to watch this play in the intimate, 80-seater theatre at Rabindra Bhavan. This highly volatile play with charged emotional content had the audience weep quietly into handkerchiefs. I watched them with the same focus as I watched the play. It felt like two performances were happening simultaneously. Ten shows in, I still wanted more.

I think that’s when my real training as a director began. Watching night after night. Understanding composition, rhythm, the spaces between words, the inner arc of the characters. That production, for me, was a masterclass in craft and emotional integrity.

Surekha Sikri and Manohar Singh in ‘Aadhe Adhure’, directed by Amal Allana.

Surekha Sikri and Manohar Singh in ‘Aadhe Adhure’, directed by Amal Allana.

The rehearsal room was sacred. Conversations weren’t casual. They were intellectual battles: about emotional memory, units and objectives, how to choreograph a pause, when breath should drop. Stanislavski and the ‘Natya Shastra’ lived together — conflicting and coexisting. I remember Sikri explaining the poetics of stillness to me over chai in the Rabindra Bhavan canteen. I was stunned by my ignorance and her generosity in sharing nuances of acting to a complete ignoramus. Manohar Singh coached me on Urdu diction, warning me not to gobble up my nuktas. These weren’t ‘sessions’. These were rituals.

What made the Repertory magical wasn’t just what we saw on stage. It was the camaraderie. The humour. The intensity. The sweat. No starry tantrums, no hierarchies. Just love of theatre. The Repertory became something deeper than a performance space. It became a place to ask — what does it mean to belong, to be an artist in India?

I believe that the ethic still pulses in the floorboards of Bahawalpur House — its studio theatres, with their bare black walls and spartan light, not compromising or pandering to meaningless spectacle. The work that one experienced in the Repertory was raw, honest. Not meant to please, but to provoke.

‘Begum Ka Takiya’, directed by the maverick director Ranjit Kapoor, offered a gentle, Sufi-tinged poeticism. It was a story about faith, belonging, and the invisible histories of Muslim India.

‘Begum Ka Takiya’, directed by the maverick director Ranjit Kapoor, offered a gentle, Sufi-tinged poeticism. It was a story about faith, belonging, and the invisible histories of Muslim India.

I recall how rehearsals under the banyan tree would spill into late-night debates about whether a character’s tears came from guilt or grief. The Repertory’s legacy is as much philosophical as it is artistic. It insists that theatre must matter — not just as art, but as inquiry. I must take a deep breath here and not let sentimental romanticism get the better of me. The Repertory has weathered storms. Shrinking contracts have undermined ensemble culture. Pedagogy is often traded for pizzazz. Government funding waxes and wanes. There’s critique — that NSD has prioritised international circuits over grassroots relevance. That critique matters. Because relevance demands friction. When no one asks questions, it means the work has stopped mattering.

Today, the question is no longer whether the Repertory is relevant. The question is: can it still surprise us? Can it continue to evolve? Has there been an ideological shift in training, in content and sensibility?

Moving slightly away from that are other serious inquires. At the heart of Indian theatre lies a deeper conundrum: what does ‘national’ even mean? Does national theatre belong only to Hindi? To Hindu mythology? Or can Tamil, Manipuri, Punjabi, Bengali, and tribal voices share that stage?

The Repertory’s history has swayed between Sanskrit classics and urban satires. But the 60th anniversary celebrations showed that this debate is far from settled. The 17-day theatre festival this past August-September was a chaotic, layered, polyphonic affair. Traditional forms jostled with post-modern aesthetics. Mahasweta Devi’s rage echoed beside Bharata’s restraint.

But many alumni and current students used the platform to ask: where are the Dalit and tribal voices? Where is the linguistic diversity? Where is the regional pulse beyond Delhi’s echo chamber?

These aren’t peripheral questions. These are vital. If the Repertory is to remain a national institution, it must reflect the full scope of India’s theatrical imagination.

The truth is that no institution, however luminous, is immune to stagnation. And yet, the very fact that the NSD Repertory remains contested is proof of its vitality. When artists still care enough to argue, grieve and demand more from an institution, it means that the institution still breathes.

As I walked past the photographs, the voices returned. Om Puri’s gravel. Surekha Sikri’s crackling intelligence. Uttara Baokar’s fierce grace. Naseeruddin Shah’s intellectual and emotional fire. They weren’t just icons. They were the scaffolding on which generations of theatre-makers stood.

— The writer is a Chandigarh-based theatre director

Arts