What Neruda means to Punjab

To write about Pablo Neruda is like writing about your family member. The name is so familiar and so close. He is an ustad, mentor and comrade to all the post-war generations of ‘progressive’ poets of Indian languages.

A well-informed poet-turned-political scientist, Prof Randhir Singh, introduced the poetry of Neruda and Hikmet to Punjabi writers, and their translations started appearing in top Punjabi literary journals like Preet Lari, edited by Navtej Singh in the early 1950s, and later in Arsee and Nagmani, edited by Amrita Pritam till the end of the century.

In Punjab, Neruda’s books in English translation were not easily accessible. For us, they were rare luxuries passed from hand to hand, usually nicked from the Panjab University library (Paris Review, Spring 1971, containing his famous interview) or gifted by Punjabi emigres, which had to be shared. I returned his tastefully designed chapbook ‘We Are Many’ (Cape Goliard Press, 1967) eventually safe to its owner after a span of 30 years.

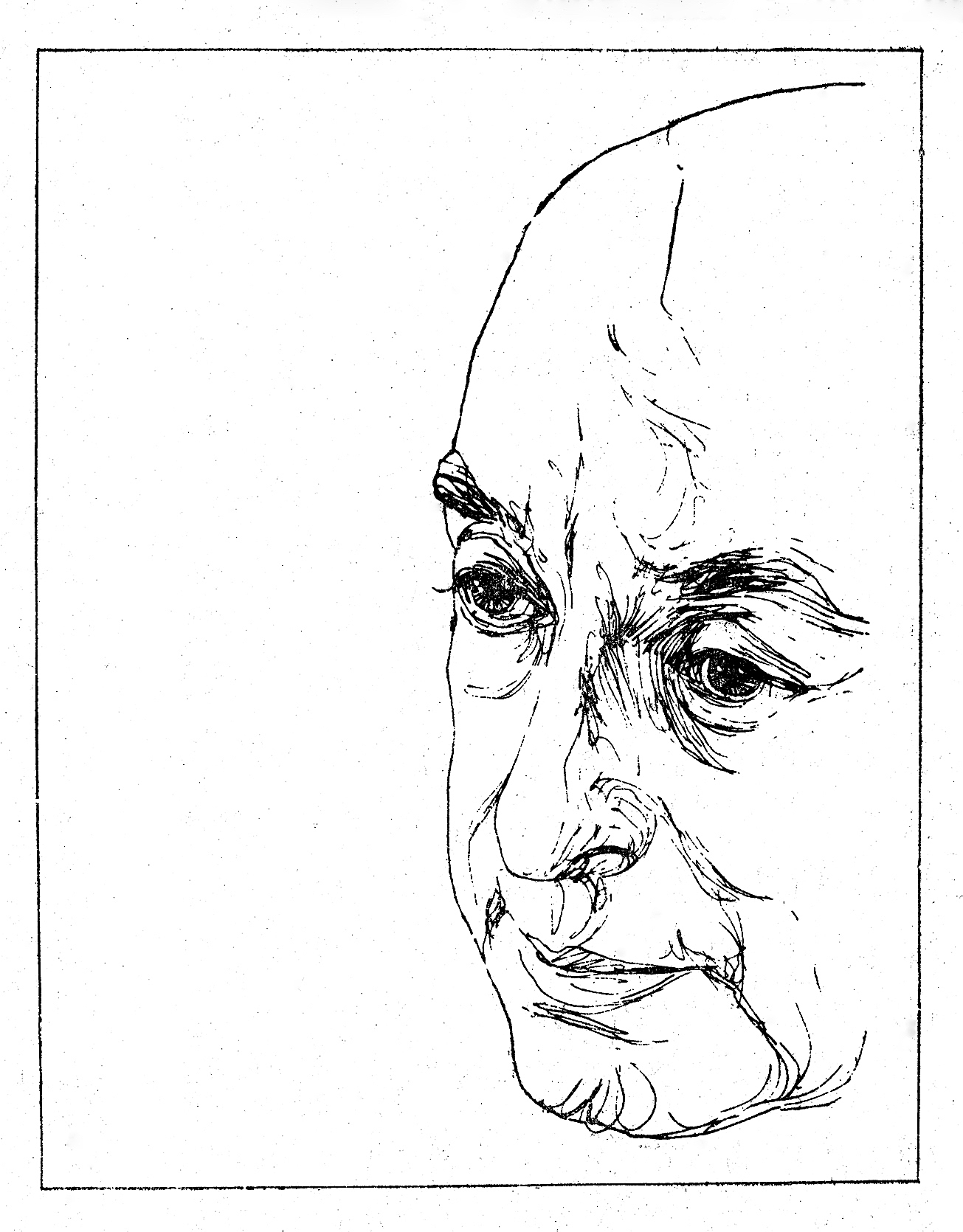

A portrait of Neruda by Imroz, 1988.

A portrait of Neruda by Imroz, 1988.

Others and I translated his many poems into Punjabi, of course from their English version. Neruda’s poem ‘The Stolen Branch’ in Punjabi from his collection ‘Captain’s Verses’ (1952) is my favourite. I read it at the Centenary Homage to him at the UCL Bloomsbury, London, in November 2004. The poetry of Neruda, Hikmet, Ritsos and Brecht works well in Punjabi translation in spite of second-hand renditions, unlike the poetry of Mayakovski and his contemporaries, not to talk of Pushkin, who is too lyrical in the original Russian to be translated into any other language.

When Neruda visited India in 1952 on behalf of the World Peace Council, though Prime Minister Nehru gave him the cold shoulder, all writers and artists of Delhi and Bombay gave him a hearty welcome. Amongst his hosts were stalwarts like Josh Malihabadi, Mulk Raj Anand, Ali Sardar Jafri and Krishan Chander. They were the founders of the Indian Progressive Writers Association, established in 1936.

Neruda’s visit ignited the literary milieu and inspired many writers to write in a new idiom. His work in blank verse also influenced my generation that started writing in the late 1960s. It carried forward the content of pre-Independence anti-colonial, social reformist, and patriotic Punjabi literature in a new form (free verse, metaphors, idiom and imagery), with the new thrust on class struggle on the model of Stalinist socialist realism.

New poets writing in Punjabi and Hindi were romantically attracted towards Maoism but there was no poet in the Chinese camp to look up to. Ironically, the pro-Russian Neruda was their role model. This self-contradiction was poetic in essence! We started writing when the Vietnam War was in its decisive phase. We thought we were the inheritors of Hikmet and Neruda. Brecht came quite late, when we had to rethink and recommit ourselves to the dialectics of art and literature.

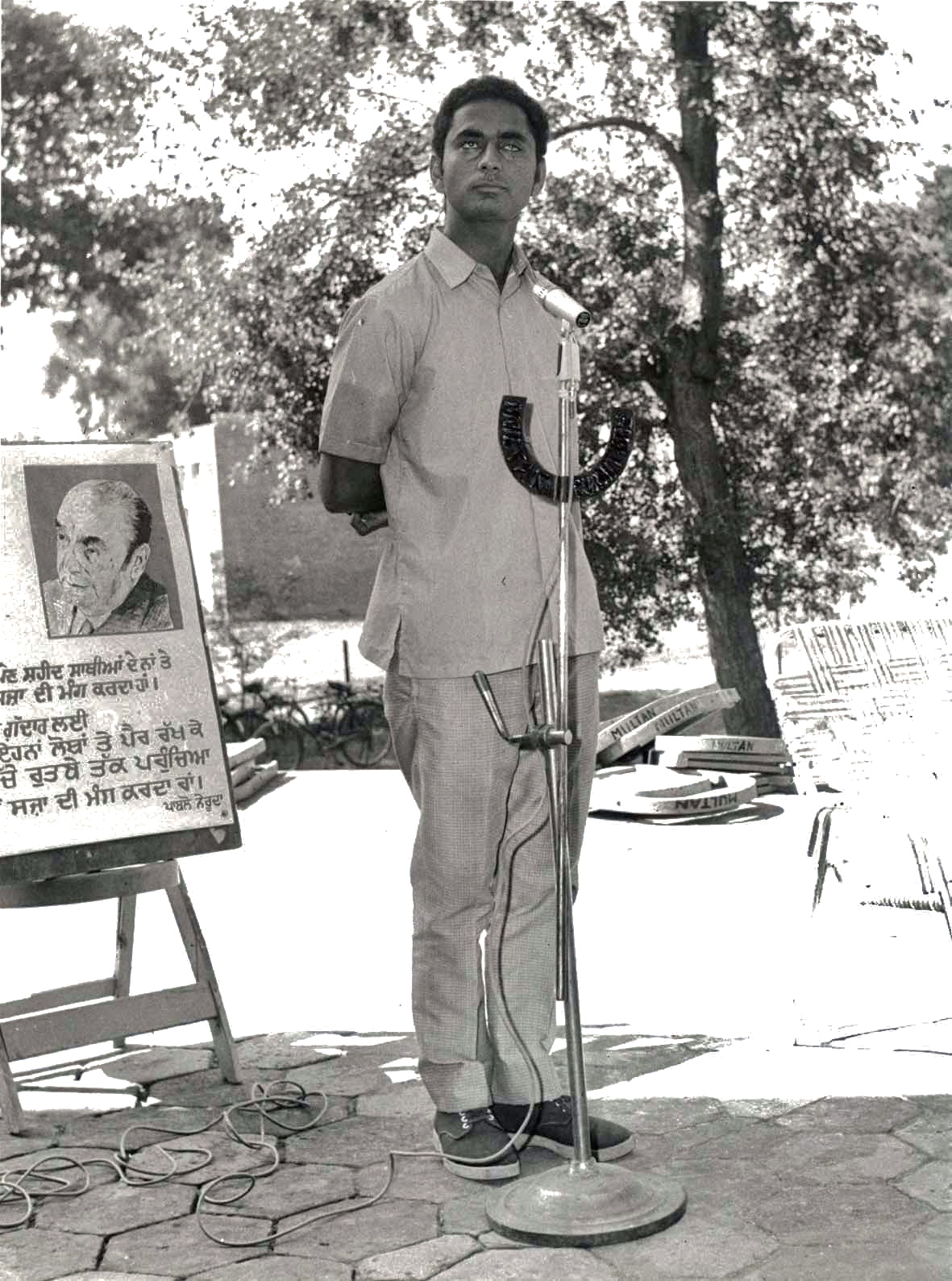

Pash reading at a Neruda memorial meeting in Nakodar in the end of September 1973. A local school drawing master made a poster of the poet with his verse: ‘Main apne shaheed sathiaan de naan te sazaa di maang karda haan’. ‘In the name of my martyred comrades, I ask for punishment…’ Photo by the writer

Pash reading at a Neruda memorial meeting in Nakodar in the end of September 1973. A local school drawing master made a poster of the poet with his verse: ‘Main apne shaheed sathiaan de naan te sazaa di maang karda haan’. ‘In the name of my martyred comrades, I ask for punishment…’ Photo by the writer

My poet friend Pash, who was assassinated in 1988 at the age of 38 by Sikh fundamentalists and came to be known as the ‘Lorca of Punjabi poetry’, used to wait for the police to arrest him and lodge him in prison, so that he could write like Neruda and Hikmet. We all availed ourselves the opportunity and wrote so many poems in prison! We used to make jokes about Neruda’s advice given to new poets not to begin with the political but love poetry: “Political poetry is more profoundly emotional than any other — at least as much as love poetry — and cannot be forced because it then becomes vulgar and unacceptable.”

In a sexually-repressed society, love was non-existent. We had to make short-cuts and the end result was dismal. Pash wrote poems in the typical style of Neruda, especially his technique of using people’s names. Pash, in a letter written from prison in 1975 (when Indira Gandhi had declared a state of Emergency) to his fellow poet Surjit Patar, told him that he (the latter) had used an image lifted from a poem by Neruda and confided that he himself had consciously copied Neruda more than him — not merely imagery, diction or feelings — and that had contributed to the development of his own sensibility. (‘Pash Deean Chitthian’, Letters of Pash in Punjabi, 1990. Edited by me).

Neruda’s poetry was the talisman of every fighter, as it was with Che Guevara while fighting in the battlefield and Soviet cosmonauts hovering around mother earth. In dark times, we are always reminded of Auden’s words that poetry makes nothing happen, but at least a good poem creates a sense of solidarity of the like-minded. It amplifies their emotions into an echo and legitimises their moral stance. A poem can’t do wonders like the genie of Aladdin’s lamp. Isn’t it enough that it holds one’s hand in the hour of need? That’s what Neurda’s poetry does.

— The writer is a London-based poet

Features