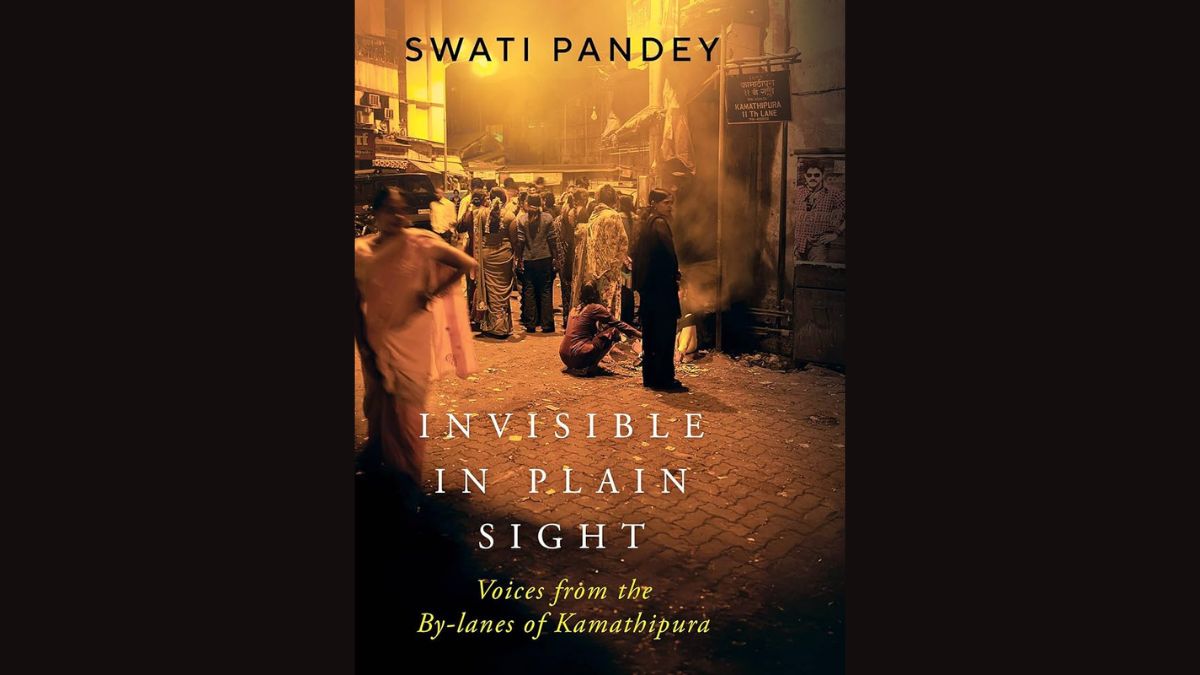

'Invisible in Plain Sight' takes readers through the psychological landscape of Kamathipura

Invisible in Plain Sight

Invisible in Plain Sight

In the heart of Mumbai’s oldest red-light district, where narrow lanes coil through layers of neglect, survival and silence, Swati Pandey finds voices that the city has long chosen to ignore. Invisible in Plain Sight: Voices from the By-Lanes of Kamathipura is not a voyeuristic peep into a world of vice; it is, instead, an act of witness. Written by a senior bureaucrat who entered Kamathipura as Postmaster General of Mumbai, the book blurs the boundaries between the official and the personal, the observer and the participant, the state and the street.

Pandey’s first encounter with Kamathipura began as a government project—an initiative to ensure financial inclusion for sex workers through India Post. But what began as a job soon became, as she writes, “a journey full of emotions; a journey of both hope and despair.” The prologue, written in a measured, almost cinematic cadence, draws the reader into the “jungle” that Kamathipura represents in her metaphor—where the laws of survival are brutal, and empathy is scarce.

Her prose is rich and visual, often tinged with the unease of someone who knows she does not quite belong to the world she is entering. Through the stories of women like Salma, Rani, and Kajol—each navigating their own precarious lives—Pandey paints a portrait of quiet resilience amid systemic violence. The women here are not moral symbols or case studies; they are complex, contradictory, alive. “I realised,” Pandey reflects in one of the book’s many self-aware passages, “that the women I was sent to serve were not victims waiting for help—they were warriors fighting every single day to protect their dignity.”

The book’s strength lies in its tone. Pandey does not romanticise Kamathipura, nor does she write from a place of moral superiority. Her training as a civil servant lends her a clarity of structure, but what truly elevates the narrative is her empathy. The bureaucratic gaze gives way to a human one, allowing her to inhabit the women’s stories without appropriating them. Each chapter, titled after an animal—The Bloodthirsty Hyenas, The Jungle is Alive, The Warm-Nested Pigeon—unfolds like a fable grounded in harsh realism. The metaphor of the jungle, while occasionally overstretched, becomes a literary spine holding the fragments together.

Pandey’s Kamathipura is not just a geographical location; it is a psychological landscape—of shame, resistance, and invisibility. The district, as she reminds us in her meticulously researched sections, is one of Asia’s oldest red-light areas, its history intertwined with colonial Bombay and the city’s own evolution as a hub of commerce and migration. Yet, her narrative is not trapped in sociology. It pulses with lived experience, drawn from conversations that linger long after they are over.

“I went there thinking I could change their circumstances,” she tells me in conversation. “But what changed was my understanding of power—who really holds it, and who quietly lives without it.”

At its best, the book reads like an ethnography with a soul. The author’s language—at once lyrical and restrained—transports readers to spaces that smell of cheap perfume and damp alleys, yet shimmer with humanity. There are moments when the book’s structure meanders, and the allegorical tone feels slightly heavy-handed. But those are small quibbles in a work that insists on seeing what others have refused to.

The photographs in the book add a crucial layer to Pandey’s narrative—transforming it from mere documentation into lived testimony. They capture not only the women of Kamathipura but also the gradual breaking of barriers between the bureaucrat and the community. In one frame, Pandey sits among a sea of women during a Milaap session on mental health, laughing and listening; in another, she ties rakhis with them, a gesture of affection and equality. A particularly resonant image shows her inaugurating the All Women Post Office in Kamathipura in 2021—an initiative that employed women from the area and gave them a new sense of dignity and belonging. Other photographs trace the outreach to children: an Aadhaar enrolment drive, and The Times of India clipping highlighting postcards made from the paintings of sex workers’ children—visual proof of empowerment finding expression in art. Together, these images turn the book into a living archive of empathy and action, showing what it means when governance touches ground.

By the end, Pandey steps back, allowing the women to reclaim the narrative. The last chapters, especially Kamathipura: A Jungle Within, are a quiet triumph—a meditation on empathy, privilege, and the uneasy coexistence of policy and pain. “If I left Kamathipura with anything,” she says, “it was a sense of humility. You can only serve people when you have first learned to see them.”

In giving these women names, memories, and moments of ordinary tenderness, Swati Pandey ensures that Kamathipura is no longer invisible. It stands, unflinching, in the reader’s line of sight—refusing pity, demanding understanding.

Author: Swati Pandey

Publisher: Aleph Book Company, 2024

Pages: 276

Price: Rs 799

Books Review