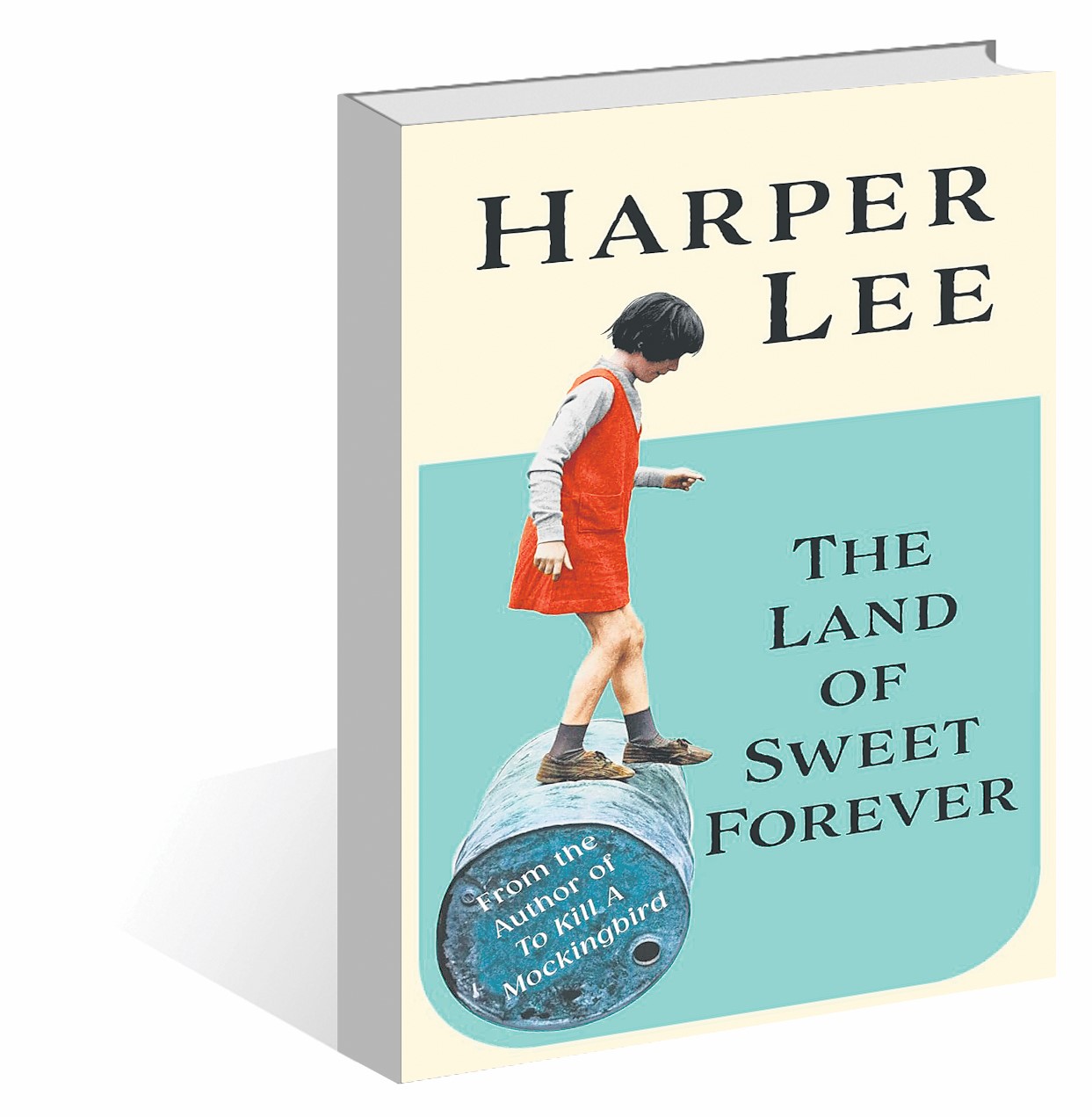

Lost & found: Harper Lee’s untold tales

The Land of

The Land of

Sweet Forever

by Harper Lee.

Penguin Random House.

Pages 200. Rs 1,299

‘I like to write,” declared Harper ‘Nelle’ Lee, author of the cult classic ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’, in her only recorded interview. It is 1964. Her southern drawl is unmistakable. Her voice is steady, strong and assured — alive. A storyteller, Harper wore shorts, smoked, golfed and never married. “Sometimes, I am afraid, I like it too much because when I get into work, I don’t want to leave. As a result, I go days without leaving the house wherever I am.”

She wrote on the typewriter given by her lawyer-editor father, AS Lee — the man who inspired Atticus Finch, the fictional symbol of American conscience. But Harper Lee never published another book. ‘To Kill a Mockingbird (TKM)’ remained a solo hit.

‘The Land of Sweet Forever’, published almost a decade after her death in 2016, is like a Christmas morning. A possibility of a conversation beyond the grave, wonderful but brief. It fills you with a longingness for more.

In 2015, another manuscript, ‘Go Set a Watchman’, was discovered, sparking controversy. Sold as a sequel, it is believed to be the first draft of ‘TKM’. Harper was living in an assisted living facility by then, partially blind and unlikely to have given consent.

‘The Land of Sweet Forever’ is a smattering of stories that she intended to publish. Eight that have never been read and eight published during different stages of her life, including a recipe for crackling bread.

She moved to New York City when she was 23. In ‘A Room Filled with Kibble’, you catch a glimpse of her in the bustling city. The narrator’s friend, Sarah Mitchell, has two dogs and is having a hard time living with herself, waking up her shrink at 3 am and banging on the door. In another story, this time not fiction, Harper spends Christmas with friends. They end up giving her a gift, a cheque for 100 dollars each month for a year, so that she can write. Her talent was just so obvious.

There is a tribute to Truman Capote. Harper travelled with him while he wrote ‘In Cold Blood’, but the two fell out. “Truman was a psychopath, honey,” she told Marja Mills, a journalist who befriended her and wrote about it.

There are glimpses of her home life. In ‘The Pinking Shears’, Miss Jean Louise Finch gives a haircut to the daughter of Mr QW Tatum, the new preacher at the Methodist Episcopal Church. “After it was all over, Daddy said it was my fault, but to this day I say it isn’t, that child had the perfect right to cut her own hair if she wanted to,” it begins. A story that sparkles with Harper’s humour, mischief and of course, an Atticus-esque lesson.

The stories aren’t perfect; in many ways, they are, as she says, in the process of being rewritten. They’re raw, bristling with life and they capture Harper as she was in the interview — young, bright, full of dreams, raring to write and hope. On being asked what next, she answered she was working on a new novel. “It is slow work,” she said. It haunts you, her voice. “I haven’t anywhere to go but down,” she told her sister once.

There is no doubt that Harper Lee was a gifted writer. But this is more than just a testament to her talent. It is also about legacy. ‘TKM’ was published in 1960 in a decade marked by white rage, race riots, lynching and violence — it offered a fable of justice, of conscience and of America. It was, after all, Scout’s version of the story. It became a success, because it offered hope. Harper won the Pulitzer in 1961, the first woman to do so since 1942.

In the book, ‘The Cat’s Meow’ confronts the question that ‘TKM’ does not, of deep-rooted prejudices. In her first draft, believed to be ‘Go Set a Watchman’, Atticus was a segregationist, unleashing outrage. Harper did trace her family to General Robert Lee, so it wouldn’t be out of place.

Segregation is at the heart of ‘The Cat’s Meow’. The narrator returns home to visit Doe, loosely based on her sister Alice, “an old-maid lawyer” who loved only three things: the study and practice of law, camellias and the Methodist Church. “He’s the only Negro I’ve ever talked to who understands what I am saying,” Doe tells her sister about Arthur, the Yankee Negro tending to her prized camellias.

“He’s had as much education as you have,” she tells Harper. He needs some getting used to, she is told. It is difficult to look past the bigotry and the discrimination.

Doe was a “deep-water segregationist, I was not and the last thing I wanted was a row which would separate me from the only family I had left. I suppose a lot of people like me have mastered the first lesson of living at home these days: if you don’t agree with what you hear, place your tongue between your teeth and bite hard”, Harper wrote.

Was this her “silent condemnation” or complicity, asks her appointed biographer Casey Cep in the foreword. This is what Harper’s legacy must hold space for — whether she was complicit, or whether she, like the Atticus that she conjured in ‘TKM’, a firm believer of equality. “I am more a rewriter than a writer,” she is quoted as saying.

Was her father, who autographed books as Atticus, the man she rewrote to be in ‘TKM’, or was he like in her first draft, ‘Go Set a Watchman’? The answer lies in what he tells Jean Louise in ‘Pink Shears’: “When you get grown up and go to law school, you’ll learn that you have to weigh the evidence and decide which party has been injured the most.”

— The writer is a literary critic

Features