Dharti Kahe Pukar Ke… Remembering Salil Chowdhury

Hindi film music fans remember Salil Chowdhury, of course. But it’s his Malayalam fans who go ecstatic recalling the musical hit ‘Chemmeen’. In Chennai, they recall his association with Balu Mahendru, while Kannada fans remember his sexy LR Eswari hits. And in his native Bengal, he is revered for both his film songs as well as his revolutionary songs, which even the Naxalites sang. As he once stated, “Film music has evolved its own national language and I can work in any Indian language.”

But if one were to ask which musical gurus did this most versatile composer train under, the surprising answer is that he had little formal training. He grew up in a tea estate in Assam where his father was a doctor and had a large collection of western music records and some Hindustani classical records. The Irish head, Dr Maloney, had British, Scottish and Irish folk songs in his gramophone collection. Salil learnt the piano and revered Mozart. He got more opportunities for listening to music in college in Calcutta and learnt Hindustani music notation in addition to western staff notation. Still, there were never any formal tuitions. Anil Biswas would call him swayambhu, one born without parents.

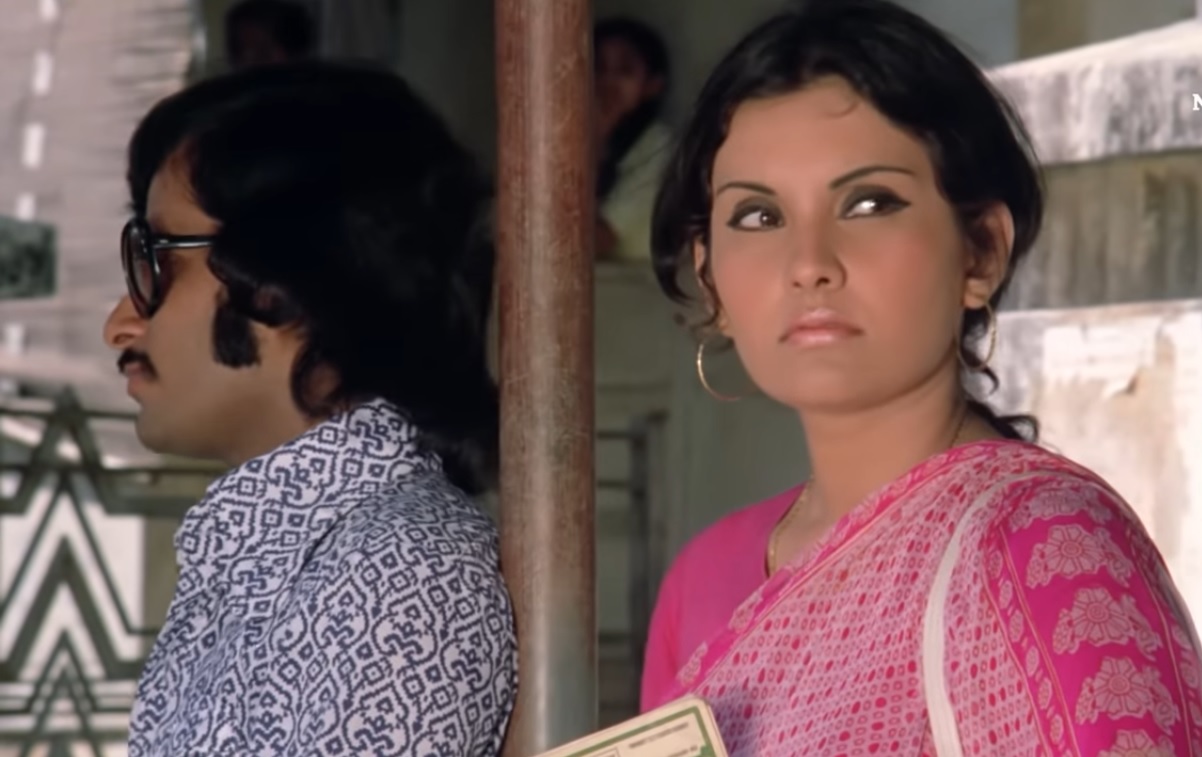

‘Na Jaane Kyun’ from ‘Chhoti Si Baat’.

‘Na Jaane Kyun’ from ‘Chhoti Si Baat’.

Salil Da became a communist and abandoned college. For two years, he was on the run, organising peasant movements. He was a member of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, and wrote revolutionary dramas, poems and songs. Almost every famous Bengali singer recorded his songs, though All India Radio had banned him. In due course, he established himself in the Bengal film industry, both as a writer and musician.

Bimal Roy called him to Bombay to write ‘Do Bigha Zamin’. Impressed, he also asked him to compose the music. Salil Da was an unknown musician then, but when he first met Lata Mangeshkar, she welcomed him and stunned him by singing one of his Bengali songs.

Salil’s Bengali songs often utilised choruses. His great innovation was to make the male and female voices sing the same melody from different starting notes. These two different tunes then blended in what western music called harmony. Sometimes, there were three different tunes being sung in what is called a three-part harmony. This had never been attempted in Bombay.

In the field of film music, Salil developed the style of counter melody or obbligato. While the singer sang the main melody, the orchestra simultaneously played a different melody and the two blended in harmony. To the ordinary listener, this was just a rich sound, but if you use headphones today, you can hear both the different melodies clearly. But the traditional composers were not impressed. Biswas declared there was no place for harmony in Indian music. The others agreed.

So, when Salil Da adapted a Soviet military march for ‘Dharti Kahe Pukar Ke (‘Do Bigha Zamin’, 1953), he gave it a chorus introduction with an alaap and in the recurring line, ‘mausam beeta jaye’, made the ‘jaye’ a typical Bhairavi melody. In the other big hit, ‘Hariyala Saawan Dhol Bajata Aaya’, he showed his deep knowledge of folk music.

But he had rarely heard Punjabi folk, so, when Raj Kapoor asked him to compose a Bhangra number for ‘Jagte Raho’ in 1956, Salil Da turned to Prem Dhawan and the resulting number, ‘Main Koi Jhut Boleya’, introduced the Bhangra to a wider audience. He continued to use Dhawan whenever he was asked to compose Punjabi type numbers.

‘Bichhuwa’ from ‘Madhumati’

‘Bichhuwa’ from ‘Madhumati’

In 1958, Bimal Roy asked him to compose for ‘Madhumati’. Every song was a hit — from the tragic ‘Toote Huye Khwabon Ne’ in a weighty Raga Darbari to a lighter Bageshwari in ‘Aaja Re Pardesi’ and folk songs like ‘Bichhuwa’ and ‘Ghadi Ghadi Mora Dil Dhadke’.

The album was a tour de force. The background score with its repeated chorus bits and motifs was outstanding. Salil Da’s songs had preludes before the vocals, which became as famous as the song melody itself. ‘Madhumati’ brought him the first ever Filmfare Award for Best Music Director and also fetched Lata her first Best Singer Award. He was flooded with offers, but accepted them indiscriminately.

‘O Sajna, Barkha Bahaar Aayi’ from ‘Parakh’.

‘O Sajna, Barkha Bahaar Aayi’ from ‘Parakh’.

Between 1958 and 1966, he did many remarkable songs, but even more outstanding film background scores. Bimal Roy’s ‘Parakh’ (1960) had one of the best Lata songs of all time: ‘O Sajna, Barkha Bahar Aayi’. But Pt Ravi Shankar criticised it for using western music with Khamaj-based melody. Salil Da advised Ravi Shankar to mind his own business. Once the Beatles became his disciples, Ravi Shankar saw merit in fusion. Later, in ‘Itna Na Mujhse Tu Pyar Badha’, Salil Da would turn a Mozart symphony theme into a Bhairavi song, outraging the purists.

The next four years, 1966 to 1970, saw Salil Da work in South Indian languages. AR Rahman, the son of his Chennai music conductor, Shekhar, remembers how astonishing it was to find a music conductor writing western notation for the orchestra and, even more surprisingly, chord charts for the guitar. Shekhar was the first musician to get a synthesiser; understandably, electronic music took birth in the Chennai studios.

Even more amazing was Salil Da’s influence on a young Ilayaraja, who played the guitar in his orchestra. His elegant orchestral arrangements evoke Salil Da’s style.

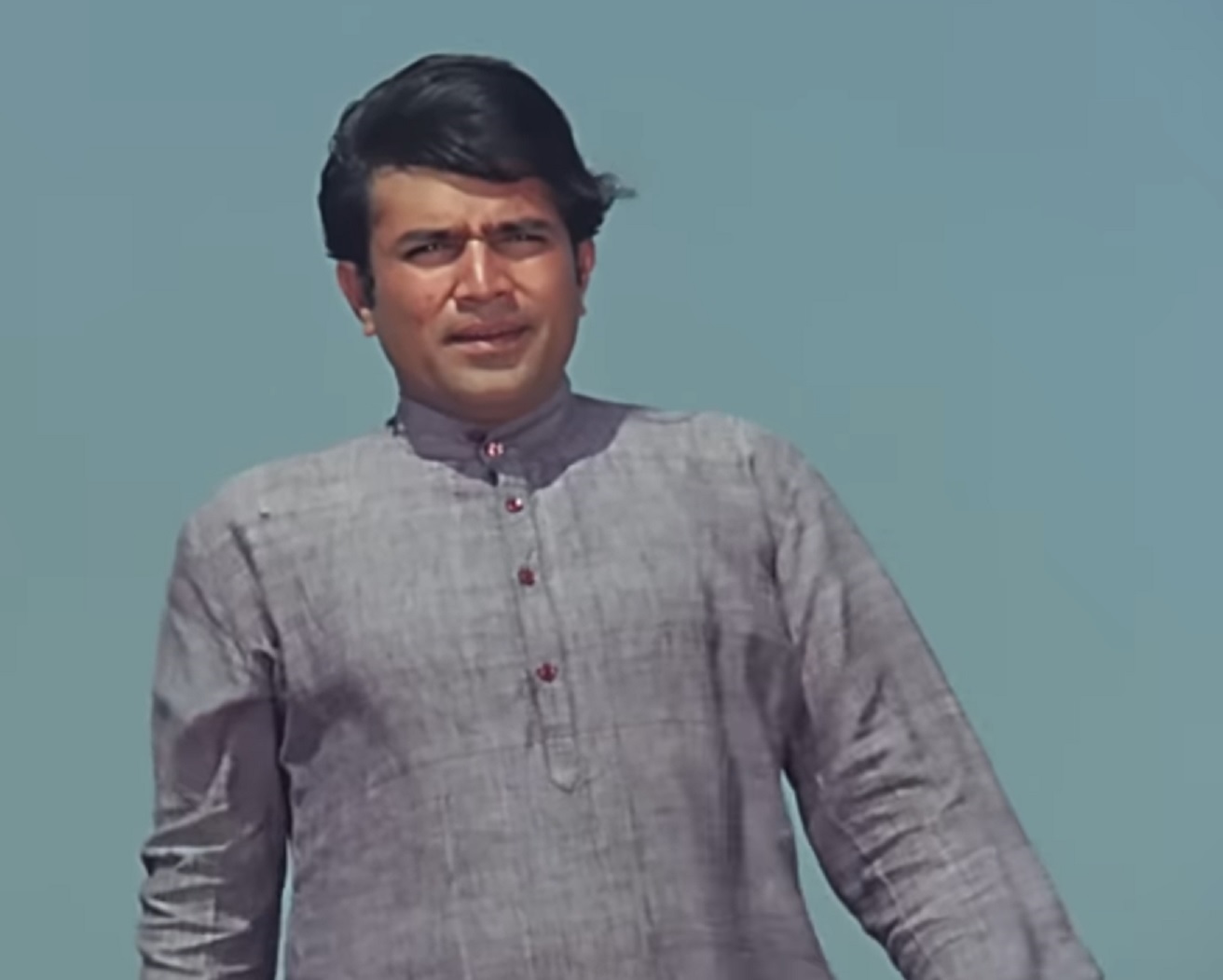

‘Zindagi Kaisi Hai Paheli’ from ‘Anand’.

‘Zindagi Kaisi Hai Paheli’ from ‘Anand’.

In 1970, Salil Da returned to Bombay for a string of Basu Chatterjee, Gulzar and other middle-of-the-road films. He composed songs without raga-based formats. Many of these are immortal. And when he wished to do raga-based songs, he mixed ragas freely. In his old age, he went back to Calcutta and set up a recording studio. Nobody before or after him earned equal fame in the North and South.

His use of western notations bridged the gap between composer and orchestra. His successors RD Burman, Ilayaraja, AR Rahman and MM Keeravani would go on to win international awards and even Oscars. This use of western notation enabled today’s composers to utilise computer software and adopt the current studio-based composition construction style. Indian film music was recognised as world music.

Salil Da began his career as a peasant revolutionary. He ended it ushering in a new revolutionary method of music making. And he achieved national integration in music. Salaam Salil Da!

— The writer served as Director General, All India Radio

Features