NCERT textbook revisions spark debate over historical accuracy

By Arindam Ganguly, OP

Bhubaneswar: In a significant but controversial shift under the National Education Policy (NEP), 2020 and the newly-framed National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCFSE), 2023, the NCERT has revised the Class VII history textbooks.

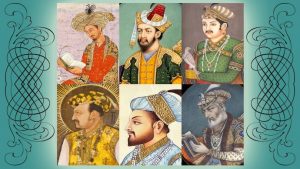

Among the most debated changes is the complete removal of chapters covering the Mughals and the Delhi Sultanate — eras that have for decades formed a core part of understanding Medieval Indian history. Among the most notable additions is a chapter highlighting India’s ‘sacred geography’ that choreographs revered religious sites such as the 12 Jyotirlingas, Shakti Peeths and Char Dham Yatra. Also, there is a stronger emphasis on government programmes like ‘Make in India’ and ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’.

While NCERT officials claim that these edits are aimed at reducing repetition and that the second volume of the textbook may provide additional context, the omission of the Mughal era from the current volume has triggered nationwide concern. Critics fear this is not a restructuring, but a rewriting of history.

Union Minister of State for Education Sukanta Majumdar has defended the move, asserting that the intent was not to erase any era but to remove repetitive content from the curriculum.

However, his controversial statement referring to the Mughal period as ‘the darkest part of Indian history’ has intensified scrutiny, prompting questions over whether ideological motivations are eclipsing educational integrity.

While a section of historians and archaeologists OrissaPOST spoke to argue that focusing on indigenous traditions and local knowledge could offer a more inclusive perspective on India’s heritage, others caution that omitting key historical periods might distort the nation’s complex and diverse history, and deprive the new generation of knowing the actual past that shaped the present.

According to noted Mumbai-based historian and archaeologist Dr Kurush Dalal, the Mughal Empire, spanning over three centuries, is more than just another chapter in India’s past. It is a foundational pillar in understanding the country’s historical, cultural, and economic trajectory, Dalal points out.

“It is sad to see that one of the most important chapters in the history of Medieval India, and a critical chapter in understanding the history, society and economy of India, has been casually rubbed out by the NCERT,” he adds. Dalal says under the Mughal reign, India accounted for nearly 24.5 per cent of the world’s GDP — a flourishing subcontinent that became the envy of Europe.

The intricate tapestry of India’s food, architecture, language, music, and even bureaucracy owes a deep debt to the Mughal legacy. It was their decline that created the vacuum exploited by European colonial powers. “In fact, it was the decline of the Mughals that allowed the Europeans to colonise us,” he notes.

To erase such an era, Dalal asserts, “borders on the criminal.” While he acknowledges the complexities of the empire — Aurangzeb’s iconoclasm being a case in point — Dalal stresses that history should be taught with ‘its light and its shadows’ not sanitised or amputated.

“We need to realise that this will result in an even more lopsided view in the minds of our children. This will also result in a very myopic view. If we want to make a course correction, we need to point out the good and the bad, and lay it clearly at our students’ desks. This cutting out of the most important dynasty in Indian History is sadly extremely unfortunate and reeks of a shortcut,” he emphasises.

Sabyasachi Nayak, an expert from the PG Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Utkal University, compares history to mathematics. “If you skip one step, your answer is wrong. So, it is with history – omit a period, or era, and the truth cannot be presented in clear terms. The narrative becomes misleading,” he says.

Nayak highlights the importance of preserving historical narratives, especially the Mughal era, which he believes is integral to understanding India’s rich cultural heritage. To drive home his point, he refers to iconic structures like the Taj Mahal and Humayun’s Tomb. “These are not just monuments, but physical chapters of our past,” he says.

Prof Sanjay Acharya, a retired History professor, agrees to Nayak’s suggestions and says that rather than erasing Mughal history entirely, the key aspects of the empires’ contributions should be retained. He, however, stresses the need for emphasising local history in textbooks. “Given that many aspects of India’s and, especially Odisha’s, regional heritage remain underexplored in education, those should be given adequate space in textbooks,” he argues.

Laxmidhar Bhol, head of History department at BJB (Autonomous) College, emphasises that conclusions on decisions made by experts should be drawn after thorough verifications. He cautions against historical bias, where the creator of a source may present a strongly skewed view, either in favour of or against a particular event, person, or regime, based on their context.

“This bias often results in unbalanced or one-sided narratives through the use of selective language or omission of facts. Such distortions should be critically examined to ensure that future generations receive an accurate and objective understanding of history,” he says.

Meanwhile, Ajit Sahoo, Assistant Professor of History at Utkal University, offers a measured voice. He believes it’s too early for blanket conclusions, noting that the second part of the textbook is still to come.

“It would be premature to draw any hasty conclusions. Although omissions have been identified in the Grade VII history textbooks, I am hopeful that the excluded portions will be incorporated into the Grade VII curriculum,” Sahoo says, adding, “In the past too, there were considerable concerns regarding the removal of certain narratives from history textbooks, but such apprehensions proved largely unwarranted.”

However, he also warns of a growing pattern of underrepresentation of Indian kingdoms and the oversimplification of complex narratives.

“In terms of impact, I believe it will be minimal, as the curriculum of a particular grade does not signifi cantly shape a child’s perception of a specific dynasty. Discussions around the elimination of the Mughal dynasty are relatively recent. However, for quite some time now, our history textbooks have tended to be somewhat dismissive of Indian kingdoms and their contributions,” he observes.

The experts agree that while the intent to diversify historical narratives is laudable, particularly the emphasis on overlooked local traditions, the method raises alarms. Rebalancing the curriculum should mean adding neglected voices, not subtracting foundational ones. India’s history is not a tale of binaries—it is a grand mosaic woven with threads of contradiction, convergence, and complexity.

In a nation as vast and varied as India, the past must not be edited to fit a present-day mould. If history must serve as a mirror, let it be one that reflects everything — flaws, glories, and all, they conclude.

With inputs from Debasish Panigrahi & Debadurllav Harichandan.

News