What Delhi, Aligarh & Glasgow Taught Me About Fixing India’s Air — With People at the Centre

Dr. Ashish Sharma holds a PhD in Civil and Environmental Engineering from the University of Surrey (UK), where his research on reducing air pollution exposure in young children gained global recognition and was featured in BBC, Forbes, and The Telegraph. He has conducted research at leading institutions including University of Surrey (UK), GIST (South Korea), Macquarie University (Australia), and the University of Toledo (USA).

Dr. Sharma has presented at major international forums such as the Cambridge Particle Meeting, IAQM (UK), World Environment Expo 2022, Smart Cities Conference New Delhi 2017, and several other conferences across Australia, Brazil, Egypt, UK, and the U.S. His expertise spans air quality, exposure science, urban sustainability, and public health. He is passionate about bridging science, policy, and community action to build cleaner, healthier cities.

Who gets to breathe — and who doesn’t?

Part 2 of a Two-Part Series on Clean Air, Citizen Science & Climate Justice

Read Part 1 here.

In India’s cities, the right to clean air is not just about pollution levels, but about privilege. While some commute in air-conditioned SUVs with filtered cabins, millions walk through smog-choked streets with no protection at all. From the footpaths of Aligarh to the policy halls of COP26, Dr. Ashish Sharma brings a rare perspective—one that blends science with lived experience, and data with deep empathy.

This isn’t just a story about air pollution. It’s about power, participation, and the everyday citizens quietly leading a revolution in how we fight for our right to breathe.

Across India’s cities, a new narrative of climate action is emerging — one grounded not in mandates but in shared knowledge, local empowerment, and behaviour-driven change. In Delhi and Aligarh, our efforts centred on building awareness and fostering citizen engagement by introducing global best practices in low-cost air quality monitoring, informed by successful community science deployments in Guildford, Surrey, and London.

Rather than merely distributing sensors, we focused on co-designing participatory frameworks to explore how citizens could collect, interpret, and act on hyperlocal environmental data. These efforts prioritised co-creation and co-implementation, enabling residents to become partners in problem-solving rather than passive recipients of information.

For Aligarh and similar small cities, such a proposed participatory approach can catalyse tangible action—students conducted green cover audits that prompted civic bodies to replant, while parents adjusted daily routines based on locally interpreted air quality trends.

In Delhi and Aligarh, we introduced global best practices in low-cost air monitoring, inspired by successful citizen science models in the UK. (Representational image source: Shutterstock)

In Delhi and Aligarh, we introduced global best practices in low-cost air monitoring, inspired by successful citizen science models in the UK. (Representational image source: Shutterstock)

This citizen-led momentum aligns with the ethos of the LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) initiative, which places individual behavioural change at the centre of climate action. As discussed in our article (Allam, Sharma, & Cheshmehzangi, 2024), LiFE represents a shift from conventional urban sustainability approaches by emphasising micro-level interventions, small yet consistent actions by individuals and communities that aggregate into systemic impact.

By rooting change in local realities, LiFE enhances existing sustainability frameworks like SDG 11 and the New Urban Agenda, creating a bridge between high-level policy ambitions and grassroots implementation.

What distinguishes LiFE is its origin as a grassroots movement in India that has evolved into an integral part of national environmental policy. Through examples like the eco-village of Piplantri, the initiative shows how community-led actions can significantly advance sustainability outcomes. Importantly, LiFE reframes the role of infrastructure, not as a standalone solution but as an enabler of sustainable behaviours, with success dependent on community participation and behavioural shifts.

In urban centres like Bengaluru, this integrated approach is already taking shape. Community-driven lake restorations and youth-led mobility hackathons illustrate how co-creation and shared responsibility are becoming central to environmental stewardship. These efforts, modest in scale but rich in civic intent, mark a cultural realignment where sustainability is increasingly embedded in the routines and choices of everyday urban life.

LiFE also reinforces the strategic synergy between technological innovation and sustainable lifestyles, particularly through its integration with initiatives like India’s Smart Cities Mission and alignment with global agendas such as the UNEA and UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development.

As our paper highlights, evaluating urban sustainability through the lens of LiFE demands a nuanced understanding of how human behaviour, urban ecosystems, and global environmental goals intersect — and how digital and interpersonal tools can be used to promote, measure, and scale sustainable habits.

From local stories to national tables: Why empathy must lead climate action

At the India@2047 conference, co-hosted by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and Harvard, I had the opportunity to take part in a closed-door dialogue on climate and health. What struck me most wasn’t just the science—it was the urgent call for empathy-led policies that truly centre people.

During our discussions, I couldn’t help but highlight a stark reality: India currently spends only about $2.5 per capita annually on air quality. Our public health expenditure stands at a mere 3% of GDP—far below what’s needed. Without adequate investment in tools that empower local governments, verify ground-level data, and engage directly with citizens, even the most well-intentioned strategies will fail to reach those who need them most.

In one of the summit’s Q&A sessions, I strongly advocated for bottom-up, empathy-driven climate finance mechanisms — the kind that support city officials and frontline workers, not just elite consultants or think tanks. Because let’s be honest: the air doesn’t wait for policy cycles. And no city can be considered sustainable if its most vulnerable residents can’t breathe freely.

“Our cities,” I said, “are marked not only by pollution but by deep environmental injustice.” Whether it’s exposure to toxic air or extreme heat, it’s always those at the bottom of the social and economic pyramid who suffer the most, while those contributing most to the problem are often the best shielded from its consequences.

Drawing from my scientific research, I pointed out that cars equipped with air conditioning and cabin air recirculation can significantly reduce in-cabin exposure to harmful particulate matter. But access to such protection in India is deeply unequal. A privileged few commute in air-conditioned SUVs with sealed cabins, while millions rely on open or poorly ventilated buses, rickshaws, or walk long distances in polluted air.

The injustice doesn’t end there. The poorest residents, often living on the peripheries of cities where pollution levels are highest, have the fewest resources to cope. Contrast this with affluent neighbourhoods—from South Delhi to South Gurgaon—where lower traffic density, better infrastructure, and greater green cover provide a protective microenvironment.

Even within homes, the gap widens. The wealthy can afford indoor air purifiers and high-end cooling systems. The middle class is still struggling to afford basic air conditioning. And the poor? They’re completely left out of this private adaptation. This isn’t just an infrastructure gap — it’s a justice gap.

That’s why I continue to push for empathetic, grounded climate action — where data informs decisions, but lived experience drives urgency. Empowering those at the frontlines, not overlooking them, must be our priority. Because a city where only the privileged can breathe safely is not a sustainable city. And until the weakest among us can live with dignity, none of us can truly claim to be resilient.

At HBS 2047, Dr Ashish Sharma met Prof Tarun Khanna to discuss inclusive, sustainable urban futures. Prof Khanna is Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor at HBS and Director of the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute.

At HBS 2047, Dr Ashish Sharma met Prof Tarun Khanna to discuss inclusive, sustainable urban futures. Prof Khanna is Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor at HBS and Director of the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute.

Representing innovation at the Bharat Climate Finance Forum 2025

I was deeply honoured to be invited as a key entrepreneur and changemaker to the Bharat Climate Finance Forum 2025 — a high-impact, invitation-only platform dedicated to accelerating India’s journey towards a Net Zero future. Sharing space with leaders from government, industry, finance, and innovation, I had the opportunity to contribute to discussions on clean technology manufacturing, climate finance, and sustainable mobility — all essential pillars of a self-reliant, climate-resilient Bharat.

At the forum, I spoke about the pivotal role that innovation-led entrepreneurship must play in shaping India’s green economy. For me, this was not just about scaling technology but advancing inclusive, sustainable development that leaves no one behind.

Dr Ashish Sharma joined the Bharat Climate Finance Forum 2025 as an invited changemaker and clean tech entrepreneur, supporting India’s Net Zero and green growth goals.

Dr Ashish Sharma joined the Bharat Climate Finance Forum 2025 as an invited changemaker and clean tech entrepreneur, supporting India’s Net Zero and green growth goals.

Deepening impact at the Global Economic Policy & Sustainability Summit 2024

Continuing my commitment to impact-driven leadership, I was also invited to speak at the Global Economic Policy and Sustainability Summit 2024, hosted at The Taj Palace, New Delhi. This ministerial-level gathering, part of the India Economic Forum, brought together a select group of thought leaders from academia, startups, global think tanks, and government.

We explored critical issues at the heart of India’s future — from unlocking climate finance and AI-powered innovation to strengthening economic resilience and building a circular economy. I was especially drawn to the summit’s emphasis on inclusive, ethical innovation and how emerging technologies can serve as tools for equitable progress.

A vision for India: Green growth, fiscal innovation & people-centric policy

Throughout the summit, I engaged in powerful conversations about mobilising India’s demographic dividend and empowering communities to drive climate resilience from the ground up. I advocated for building robust fiscal frameworks that support innovation while ensuring that growth doesn’t come at the cost of ecological integrity.

These forums reinforced a truth I deeply believe in: India has the potential not just to envision the future of climate leadership but to actively build it through collaboration, entrepreneurial spirit, and inclusive and bold policymaking.

Dr. Ashish Sharma at the Global Economic Policy & Sustainability Summit 2024, New Delhi — Invited delegate in a ministerial dialogue on AI, climate resilience & green growth.

Dr. Ashish Sharma at the Global Economic Policy & Sustainability Summit 2024, New Delhi — Invited delegate in a ministerial dialogue on AI, climate resilience & green growth.

The long view: Short-term fixes vs lasting solutions

In response to critical air quality episodes, cities like Delhi have implemented contingency measures such as the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) Stage 4. While essential in acute scenarios, such reactive interventions underscore the need for long-term, systemic reforms grounded in institutional capacity and regional coordination.

To move beyond episodic management, we must prioritise the following:

- Regional air-shed governance: Air pollution is not confined by administrative boundaries. A coordinated strategy across Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh is essential to address transboundary emissions and align mitigation efforts.

- Institutional strengthening: Pollution Control Boards must be equipped with statutory autonomy, adequate human resources, and technical capabilities to monitor, regulate, and enforce environmental standards effectively.

- Nature-integrated infrastructure: Strategically designed urban green spaces—including tree canopies, bioswales, and buffer zones—play a critical role in reducing particulate matter, regulating microclimates, and enhancing ecological resilience.

- ESG integration for MSMEs: Embedding Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks within small and medium enterprises is key to diffusing sustainable practices across India’s industrial base, which is often overlooked in regulatory discourse.

- Human-centred urban design: Cities must be envisioned around the needs of their most vulnerable residents—children, the elderly, and low-income communities. This entails the development of inclusive mobility corridors, accessible public spaces, and transit ecosystems that prioritise safety, dignity, and environmental integrity.

Where tech meets trees: The future is hybrid

At the World Environment Expo, I examined the intersection of emerging technologies and nature-based solutions (NBS), highlighting the potential of artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), and blockchain to enhance urban ecological resilience. These technologies can enable predictive analytics for pollution patterns, optimise irrigation for urban green infrastructure based on real-time meteorological data, and ensure transparency in environmental monitoring through decentralised data systems.

However, while digital tools offer valuable efficiencies, their effectiveness ultimately depends on the design and governance models underpinning them. Nature-based solutions yield the greatest long-term impact when they are embedded within community priorities, reflect local ecological knowledge, and are adapted to specific environmental and socio-cultural contexts.

Whether in the form of urban forests, bioswales, or rooftop farms, such interventions must evolve organically through co-creation and stewardship, not simply as technocratic installations. Dr. Sharma was felicitated by Bhavisha Buddhadeo, founder of Rootsaps, in recognition of his environmental leadership at the World Environment Expo (WEE 2022).

At the World Environment Expo, Dr. Ashish Sharma explored how AI, IoT, and blockchain can boost urban ecological resilience through nature-based solutions.

At the World Environment Expo, Dr. Ashish Sharma explored how AI, IoT, and blockchain can boost urban ecological resilience through nature-based solutions.

Lessons from abroad, tailored for home

The experiences of global cities such as London and Los Angeles offer instructive precedents. London’s substantial air quality improvements were driven by integrated transport reforms, congestion pricing, and sustained public engagement. In contrast, Los Angeles’s decades-long battle against photochemical smog underscores the importance of long-term regulatory enforcement, technological innovation, and inter-agency coordination.

While these examples offer valuable insights, India’s environmental trajectory must be shaped by its unique socio-economic, demographic, and infrastructural realities. Localised policy innovation, informed by global best practices yet rooted in domestic priorities, will be central to addressing the scale and complexity of India’s urban environmental challenges.

Mechanisms such as the $300 billion COP29 climate adaptation fund present a significant opportunity to support transformative change. However, access to such finance will depend not only on strategic alignment with global frameworks but also on demonstrable local preparedness through robust implementation, institutional capacity, and inclusive planning processes.

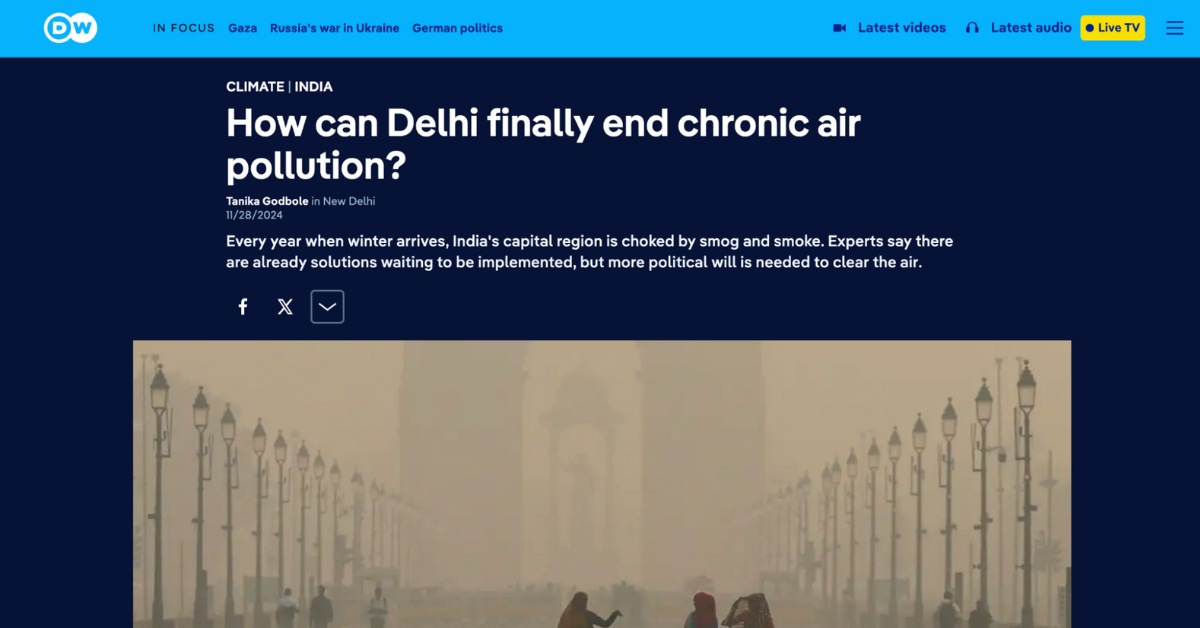

In this context, the chronic smog problem in Delhi serves as a case in point. As highlighted in this DW article, while proven solutions exist, their success hinges on sustained political will, institutional coordination, and public engagement. With each winter’s return of hazardous air, the urgency for action intensifies — not just to replicate global solutions, but to adapt them effectively within India’s complex urban landscape.

While proven solutions exist, their success hinges on sustained political will, institutional coordination, and public engagement.

While proven solutions exist, their success hinges on sustained political will, institutional coordination, and public engagement.

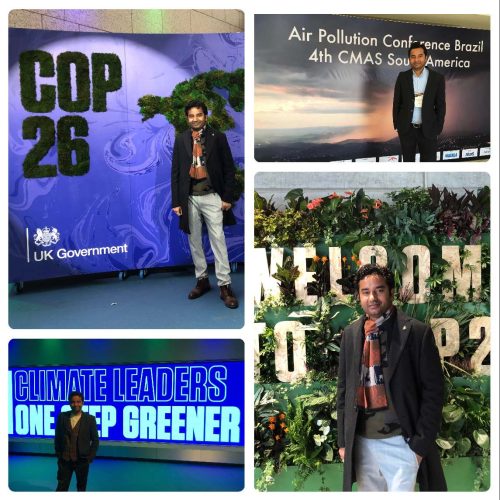

One step at a time: What COP26 taught me

Attending COP26 in Glasgow marked a pivotal moment in my professional journey. When I attended COP26, I had no institutional badge. Without institutional sponsorship, I chose to self-fund the experience, driven not by obligation but by a personal conviction to participate in a global dialogue on climate action.

Lodging in modest accommodations and navigating the city through shared transport, I found that some of the most meaningful exchanges emerged not within formal plenaries, but in the margins — through unscripted conversations, spontaneous collaborations, and the shared aspirations of peers from across the world.

This experience reaffirmed a deeper truth: transformational change does not always originate in structured forums or institutional privilege. It often begins with the willingness to step beyond certainty—into dialogue, vulnerability, and collective visioning. It is within these spaces of intent and human connection that impactful action often takes root.

Dr Ashish realised that transformational change often starts not in formal forums, but in open dialogue, vulnerability, and a shared vision beyond certainty.

Dr Ashish realised that transformational change often starts not in formal forums, but in open dialogue, vulnerability, and a shared vision beyond certainty.

What cities must do now

Here are my key recommendations for any city serious about sustainability:

- Strengthen legal frameworks: Empower local regulators to act.

- Enhance monitoring: Use low-cost tech, and make the data public.

- Public health impact narrative in clean air policy: Emphasise the quantified public health consequences of particulate matter exposure. These efforts should leverage epidemiological evidence showing how PM2.5 and PM10 exposure increase asthma, heart disease, and early deaths. Quantifying these health costs strengthens the case for urgent action since clean air isn’t just an environmental goal; it’s a public health necessity.

- Grid decarbonisation: Advocating for increasing renewables in electricity used across the city.

- Life cycle thinking in EV strategy: Encouraging informed decision-making beyond just tailpipe emissions.

- Fund grassroots projects: Small grants, big change.

- Embed climate in classrooms: Let kids lead.

- Reward green innovation: Especially from startups.

- Cross-ministerial action: Break silos between MoEFCC, MNRE, MoHUA.

- Adopt LiFE: Promote climate-friendly habits—walking, saving energy, growing food.

Citizen science is a culture, not a campaign

Citizen science, when embedded within local ecosystems, is more than a data-gathering tool—it becomes a catalyst for informed civic participation.

Our pilot projects in Aligarh and Delhi demonstrate how community-led monitoring can bridge the gap between environmental data and actionable change:

- Building Capacity for Local Monitoring: With structured training and low-cost sensors, residents gained the ability to monitor air quality in real time, producing localised datasets often missing from official reporting systems.

- Data-Driven Decision Making: Exposure to real-time pollution readings prompted behavioral shifts. Parents altered daily routines, and students conducted green cover audits, which informed community-led interventions.

- Community-Led Accountability: Equipped with verifiable data, citizens engaged constructively with municipal authorities, shifting the dynamic from passive concern to evidence-based advocacy.

- Tangible Outcomes: These efforts led to measurable actions, including tree plantation drives, targeted traffic rerouting, and increased responsiveness from local bodies to citizen concerns.

By treating citizens as co-producers of environmental knowledge, not just observers, we unlock a powerful mechanism for urban resilience. Empowered communities don’t wait for change; they initiate it.

The last word: This is personal

As Mahatma Gandhi said, “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.” I believe urban sustainability isn’t a distant goal but a necessity. It lives in the air we breathe, the parks we visit, and the futures we choose.

I have not just studied air pollution—I’ve chased it, fought it, breathed it, and, above all, worked to design tools and trust so that others wouldn’t have to fight alone.

Every cleaner breath is a quiet revolution. Let’s make sure everyone gets to take one.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily reflect or represent the official positions, policies, or views of any organisation, employer, or affiliated institution.

Edited by Leila Badyari

News