After Floods Destroyed Their School, Sustainable Design Gave a Tribal Village in Maharashtra a School Like No Other

The walls were cracked. The floor – damp and crumbling. Inside the dim classrooms of Saraswati Vidyalaya in Kelthan village, Mumbai, Maharashtra, 120 children sat hunched over their books, trying to focus as monsoon winds howled outside and the roof above them leaked. There was no proper lighting, no ventilation, and barely any space that felt safe.

Yet, every day, they came back. Why? because this was the only school they had.

Then came the floods.

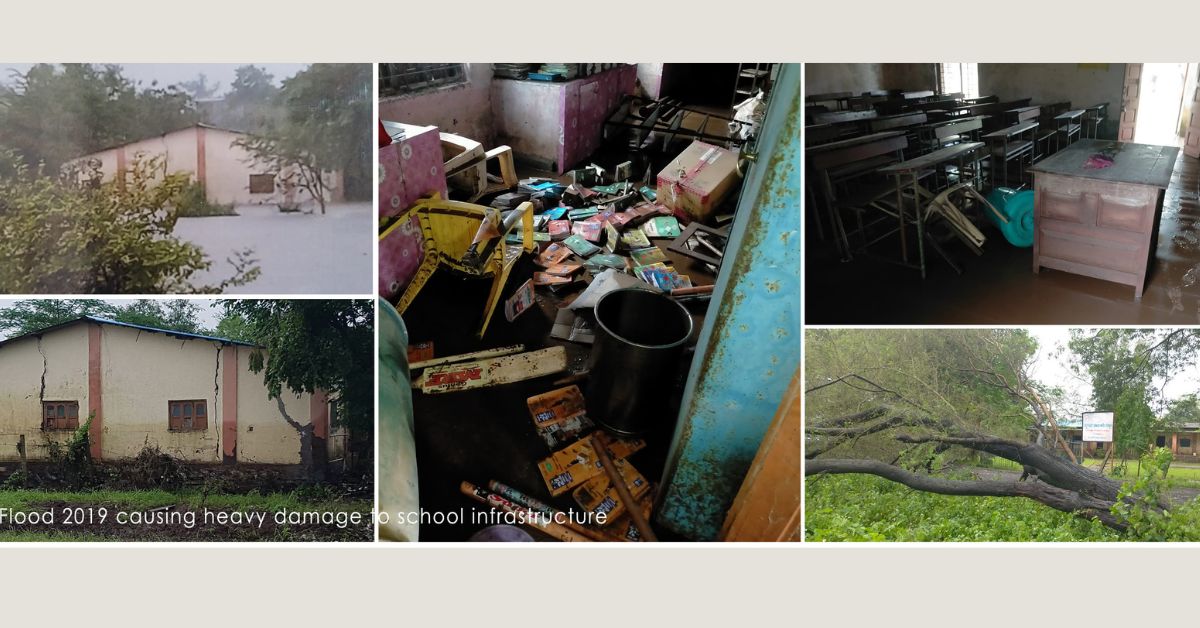

In 2019, rising waters from the nearby Tansa river swept through the school, soaking classrooms and washing away books, computers, and lab equipment. Water stains marked the high tide of the disaster, a permanent reminder of what little was left behind. The classrooms were no longer safe, but the children came anyway.

It was this harsh reality that moved architects Gauri Satam and Tejesh Patil, co-founders of unTAG Architecture and Interiors, to take action. What started as a personal calling soon became a community-led mission to rebuild the school not only stronger, but smarter, greener, and deeply rooted in the culture and climate of its surroundings.

A school started out of necessity

The story of Saraswati Vidyalaya begins long before the floods. It was born out of a deep belief that every child, no matter how remote their village or modest their background, deserves access to quality education.

“In 2001, we didn’t even have a building,” shared Principal Vijay Ramesh Patil, who helped establish the school under the Devgarh Vibhag Shikshan Prasarak Trust. “We started with a single room given to us by a social worker in the village. Just one room, a handful of students, and two teachers.”

While the infrastructure was tampered with by the floods, the students showed up to school purely because of the urge to learn.

While the infrastructure was tampered with by the floods, the students showed up to school purely because of the urge to learn.

Eventually, the trust secured land near the Tansa River, and a modest structure was built to house Classes 8 to 10. But the school’s proximity to the river came at a cost. Every year, monsoons brought with them the same story: rising waters, destroyed classrooms, and equipment damaged beyond repair.

“Five to six feet of water would enter the rooms,” Patil recalls. “Parents were worried. Cracks began to appear in the walls. It became too dangerous, and we were left helpless.”

Learning Space Foundation: A ray of hope

In 2020, in desperate need of a solution, the school approached Learning Space Foundation, a prominent NGO in the locality. That connection led them to Tejesh Patil and Gauri Satam of unTAG Architecture and Interiors — both of whom had strong rural roots and a passion for socially conscious design.

“They didn’t charge us anything,” says Patil. “They treated this as social work. They listened, understood the school’s needs, and began planning a rebuild.” What followed was a collaborative, community-driven process to reimagine the school, not just as a safer structure, but as a model of sustainable, inclusive architecture.

The design evolved during the pandemic and was rolled out in two phases. Phase one focused on building core necessities: three well-ventilated, sunlit classrooms, a staff room, and toilets on the first floor, with a kitchen and gathering space below. All of it was made with locally sourced materials and built with techniques that reduced cost and environmental impact.

‘A design rooted in context, culture, and climate’

From the beginning, unTAG’s vision for Saraswati Vidyalaya was grounded in sensitivity to both the place and its people. The team didn’t arrive with grand blueprints or off-the-shelf solutions. Instead, they immersed themselves in the local aesthetics, traditions, and climate to create a design that resonated with the tribal children.

“We don’t believe in creating monumental designs in rural settings,” says Tejesh. “We believe in conscious architecture — one that respects the region’s climate, budget, and culture. That’s what drove every decision on this project.”

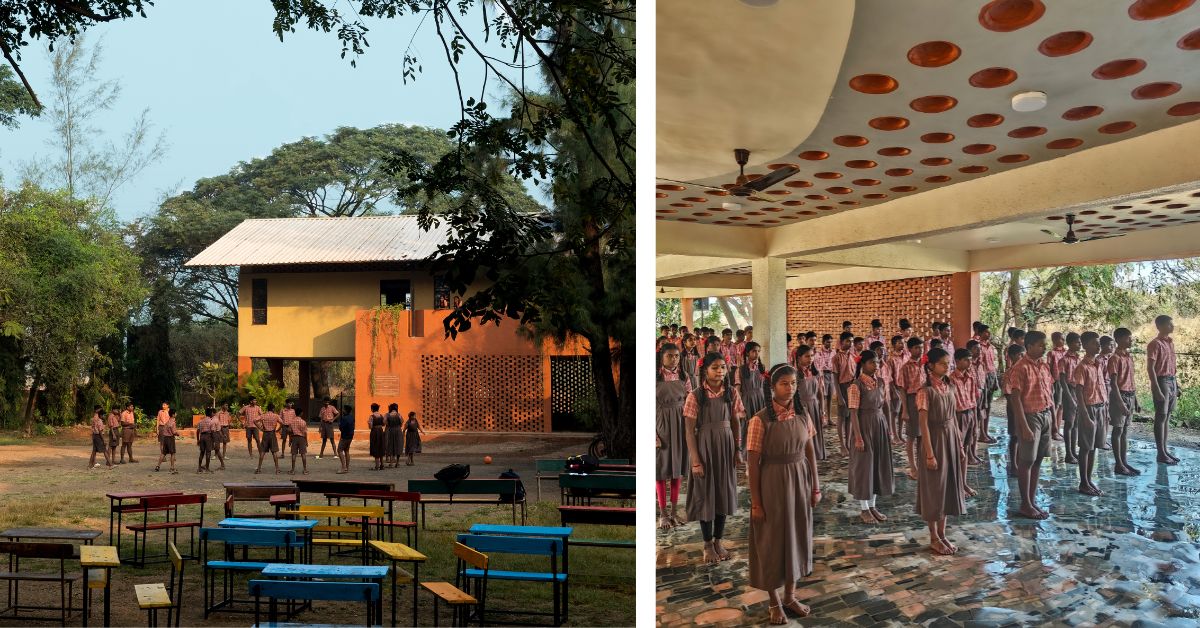

The first major step was to reimagine how the school interacted with its flood-prone site. By elevating the entire built structure onto stilts, the design offered a dual benefit: classrooms were now safe from flooding, and the open space below became a flexible community area. This ground floor now hosts school activities, medical camps, and community gatherings, offering a space that is both protected and productive.

Every material tells a story

The team’s material palette was shaped not in faraway showrooms, but by the resources and craftsmanship available within a 25-kilometre radius. Locally baked red bricks became the star material, not just used traditionally, but innovatively.

“We used a technique called rat-trap bond,” Gauri explains. “It involves laying bricks with a vertical gap, which reduces the number of bricks used and adds thermal insulation. It’s cost-effective and perfect for our climate.”

The rat-trap bond technique reduces the usage of bricks while providing a good pattern.

The rat-trap bond technique reduces the usage of bricks while providing a good pattern.

The same bricks were also used to create brick jaalis — perforated screens that allow light and breeze to filter through, adding texture, rhythm, and natural ventilation without extra cost. “It also adds privacy on the ground floor,” shares Gauri.

A filler slab technique was employed in the ceiling, embedding handcrafted earthen discs made by local artisans. This wasn’t just a nod to the region’s pottery traditions; it also reduced the amount of concrete used, lowering both carbon footprint and construction cost. “It adds vernacular beauty while being functionally efficient,” says Gauri.

Even the flooring told a story. The ground floor was laid using upcycled Indian stone — offcuts and scraps from local vendors, collected free of cost and sorted by the students themselves. These stones were arranged in a flowing pattern inspired by the nearby Tansa River, turning discarded fragments into a vibrant visual metaphor.

Green at heart, in every sense

Sustainability didn’t end with structure. unTAG integrated solar panels to make the school self-reliant in energy, added planters along the façades that students now care for, and left the school ground unpaved to allow rainwater to percolate naturally. Portions of the land were also converted into vegetable beds, growing seasonal produce used in the school’s mid-day meals.

“This is called biophilic architecture,” says Gauri. “We wanted children to feel connected to nature, to see themselves as part of an ecosystem. When they care for a plant or harvest vegetables they’ve grown, it changes the way they relate to the space.”

Cross-ventilation, north-facing skylights, and sloped roofs further ensured that the school remained thermally comfortable and naturally lit year-round. These passive design strategies eliminated the need for artificial cooling or lighting during the day.

Built smart and affordable

The most astonishing aspect of the Saraswati Vidyalaya rebuild was its cost-efficiency. “We managed to keep the cost at just Rs 1,200 per square foot,” says Tejesh. We achieved this through smart material choices, local labour, and reusing what others might discard.”

The local materials sourced within 25 km radius helped to reduce cost drastically.

The local materials sourced within 25 km radius helped to reduce cost drastically.

Instead of hiring expensive urban contractors unfamiliar with alternative techniques, unTAG trained local builders directly on-site. “We created mock-ups, taught them how to lay bricks, how to follow the flooring pattern,” Tejesh explains. “It was challenging, but it saved money and it left the community with new skills.”

This hands-on approach not only reduced cost but also instilled a sense of ownership among the locals. Even the students contributed through shramdaan (voluntary work), which added to the spirit of collective building.

Taking pride in where they learn

By the end of 2023, Phase 1 of Saraswati Vidyalaya’s transformation was complete. What now stands on the banks of the Tansa River is not only a structurally resilient school, it is a space that radiates dignity, purpose, and joy.

“The difference is visible in the children’s eyes,” says Patil. “Earlier, they studied in a space that looked like a cowshed. Now, they walk into these bright, breezy classrooms with pride. The environment itself inspires learning.”

The school has already seen an increase in student enrollment. From just 120 students, the number has grown to nearly 200, and continues to rise. “Parents who once hesitated to send their children now feel confident,” says Patil. “The stigma around rural government schools is fading. This building gave us that credibility.”

The new design of the school has brought in confidence among the students and teachers.

The new design of the school has brought in confidence among the students and teachers.

This transformation has also been officially recognised. Saraswati Vidyalaya recently received third prize in a statewide competition organised under the Chief Minister’s school excellence initiative, winning Rs 1 lakh and earning acclaim for both its educational and architectural merit.

The project’s success was made possible by a network of generous donors and empathetic institutions. Learning Space Foundation played a pivotal role in mobilising support and linking the school with organisations like Universal General Insurance Company, which contributed Rs 9 lakh to kickstart construction.

Later, Jamnabai Narsee School in Mumbai stepped in with funding, furniture, and by fostering beautiful exchange of ideas and values. Their students raised funds and visited Kelthan to understand rural education realities better, bridging a rarely crossed gap between urban and rural worlds.

“It was like a barter system,” says Gauri. “City students gave their time and resources, and in return, they received a grounded, eye-opening experience. It was about connecting the dots — and it worked.”

Phase 2 and beyond

The work, however, isn’t over. unTAG has already completed the design for Phase two, which includes expanding the school to accommodate skill-based education for Classes 11 and 12, in line with the National Education Policy. The team is now actively seeking donors and partners to help realise this next phase.

“This is not just about one school,” says Tejesh. “Our goal is to create a replicable model — an ecosystem of rural schools that are sustainable, beautiful, and deeply rooted in their context.”

For Gauri and Tejesh, who both have rural connections, the project is personal. It is a fusion of passion and profession, a belief that good design should be accessible, that architecture can be an agent of social change.

“We believe every building should resonate with its environment,” Gauri says. “And every child deserves to learn in a space that respects their identity, culture, and future.”

In Saraswati Vidyalaya, that vision has taken root — brick by brick, with care, consciousness, and community at its core.

Edited by Vidya Gowri Venkatesh. All images credit unTAG.

News