World Sickle Cell Day | What India needs to do to eliminate this genetic blood disorder by 2027

Representative Image

Representative Image

As we observe World Sickle Cell Day on June 19, it is worth taking stock of the country’s bold and ambitious national mission, launched two years back, to eliminate sickle cell disease (SCD) by 2047, the centenary of India’s independence.

India carries the second-highest burden of SCD globally, and turning this vision into reality requires not just political resolve but also sustained public-private partnerships, grassroots community engagement, and significant investments in awareness, early diagnosis, and comprehensive care. World Sickle Cell Day serves as a critical reminder of the urgency and scale of the National Sickle Cell Elimination Mission.

What is sickle cell disease?

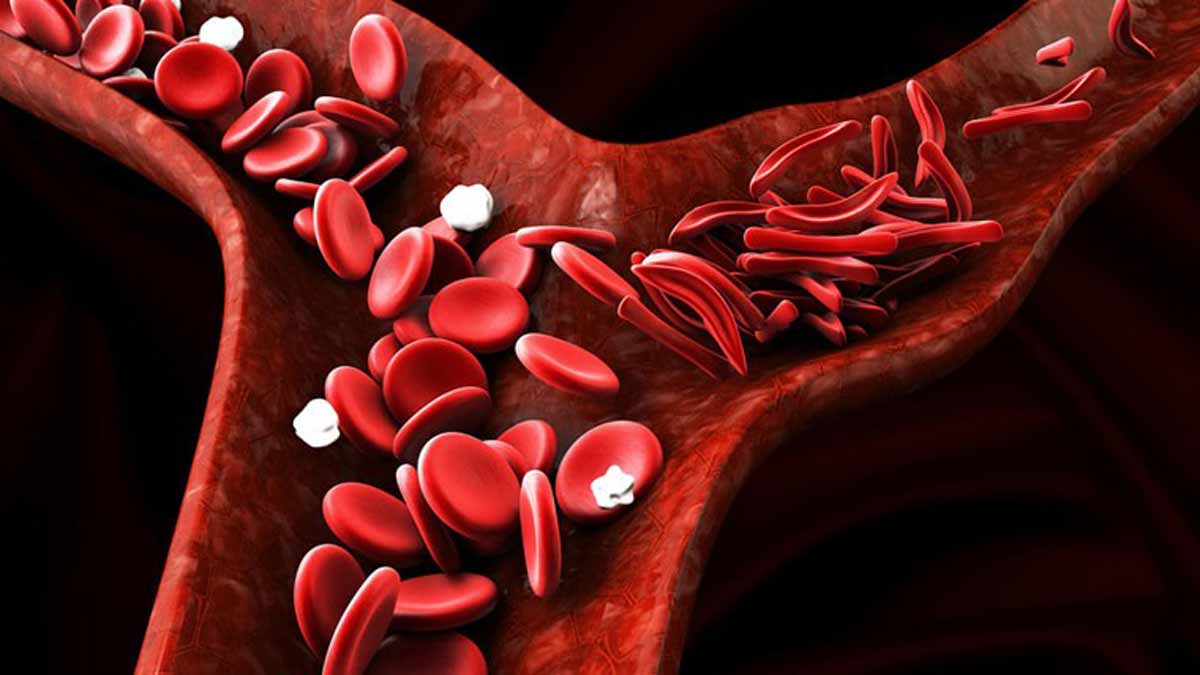

Sickle cell disease is a genetic blood disorder that affects the haemoglobin in red blood cells, causing them to assume a sickle shape, which restricts blood flow and leads to severe pain, infections, and organ damage.

In India, it predominantly affects tribal populations across states such as Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh. According to estimates, over 20 million people carry the sickle cell trait, and nearly 30 thousand children are born with the disease each year.

What makes this battle so complex is the intergenerational nature of the disease and the social marginalisation of affected populations. Poor awareness, cultural stigma, limited access to healthcare, and late diagnosis compound the human and economic toll.

When launched two years ago, the mission set a bold target of screening 7 crore people by 2026. So far, about 5 crore people have been screened across 17 high-prevalence states, but there is still a long way to go.

While there have been real infrastructure gains, including new labs and counseling centers, treatment access continues to lag, with only 18% of patients receiving consistent care. The commitment to awareness and research has shown encouraging progress through public campaigns and the CSIR initiative. However, challenges like lingering stigma associated with the disease, funding gaps, and data inconsistencies continue to hinder progress.

The mission has made a promising start, but the road to 2047 will require sustained resolve and consistent efforts to achieve its grand vision.

This is where public-private collaboration becomes critical. Non-profits and private hospitals can play a vital role in outreach, counselling, and capacity building at the last mile. Biopharmaceutical companies can help scale low-cost diagnostics, gene-based therapies, and drug distribution — especially in districts underserved by the public health system.

For example, private labs can support mass screening using portable diagnostic kits, while telemedicine startups can bridge the gap in specialist care. Pharma companies can collaborate with the government to ensure a stable supply of hydroxyurea and invest in local manufacturing of cutting-edge gene therapies.

Culturally sensitive awareness campaigns can help destigmatise the disease. Media can play an important role in educating people about the disease. Even corporate CSR efforts can be aligned to fund community health workers, transport for rural patients, and school-based screening drives.

Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT), an established and curative treatment for sickle cell disease, has shown remarkable success rates, especially in younger patients. With the right infrastructure and donor matching, BMT offers the possibility of a complete cure. As part of a broader collaborative effort, this treatment modality can also be made more accessible to those who need it most, particularly in underserved tribal regions. Through partnerships between government health systems, private hospitals, and research institutions, it is possible to scale up transplant facilities, encourage donor registries, and subsidise treatment costs.

Public-private collaborations can ensure that both prevention and cure are no longer a privilege of a few but are available and accessible to all those in need.

Dr Gaurav Kharya is a paediatric haematologist and a bone marrow transplant specialist in New Delhi. He is also a researcher innovating cell therapy solutions.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK

Health