How a Scientist Is Growing Bamboo Forests To Heal Maharashtra’s Villages Choked by Toxic Ash

In this column, TBI editorial brings you articles from experts across India, tackling the challenges that matter most. These insightful pieces offer practical solutions and inspire us to take proactive steps in addressing the issues we face in our communities and beyond.

As narrated by expert Dr Lal Singh, Principal Scientist and Project Leader at CSIR-NEERI. He specialises in ecological restoration, particularly using bamboo for environmental rehabilitation of degraded lands such as fly ash dumps, mining sites, and wastelands.

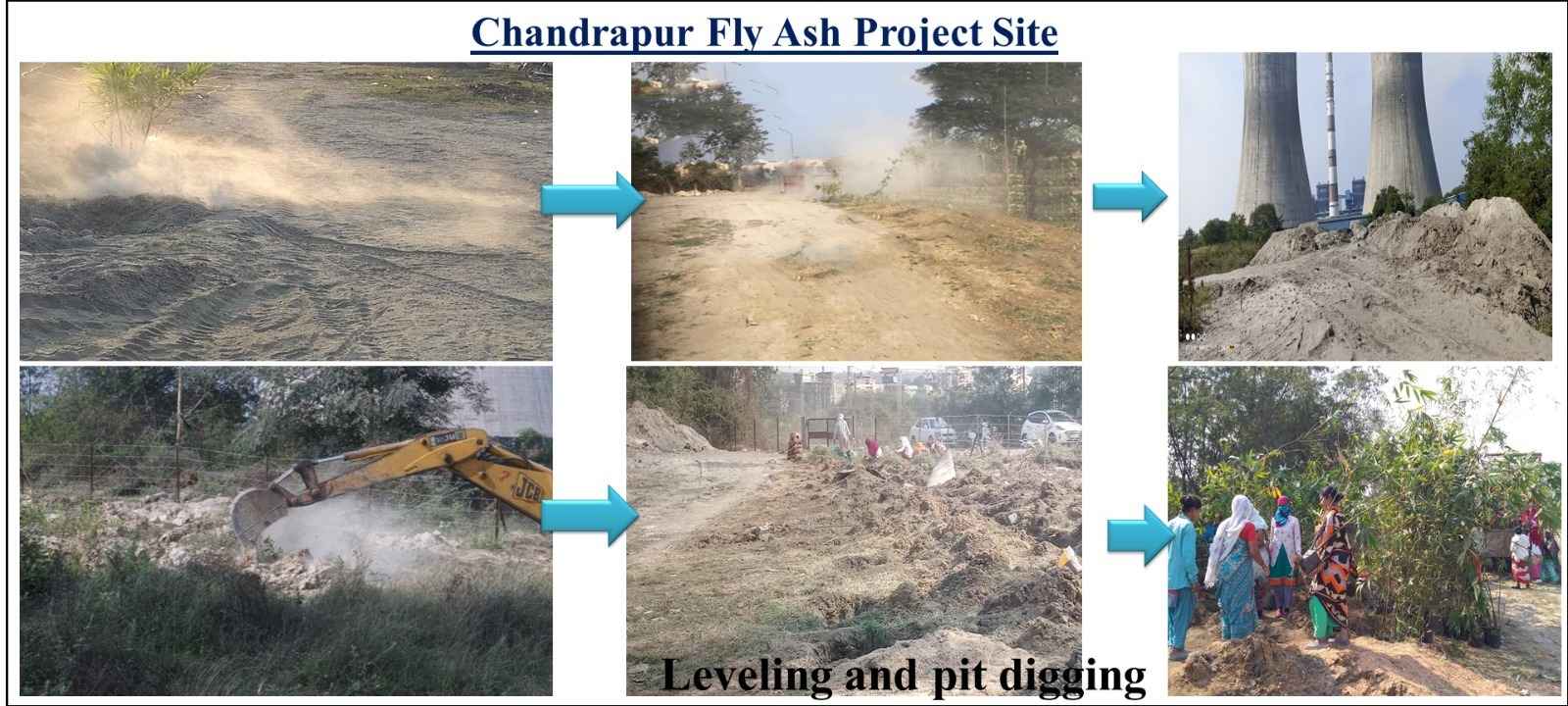

There was a time when this land looked like the surface of the moon—grey, dry, and covered in thick layers of fly ash. Nothing could grow here. The soil was weak, the air heavy with dust, and the ground cracked underfoot. For years, people believed these areas around Koradi, Khaparkheda, and Chandrapur Thermal Power Stations in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha district were beyond saving.

But today, everything has changed. The dusty ground is now covered with soft green grass. Long lines of bamboo plants, neem, karanj, and other native trees stretch as far as the eye can see. Some trees now stand as tall as buildings, their leaves rustling in the wind. Where there was once silence and emptiness, there is now shade, cool air, and the sound of birds returning.

Where there was once silence and emptiness, there is now shade, cool air, and the sound of birds returning.

Where there was once silence and emptiness, there is now shade, cool air, and the sound of birds returning.

This transformation didn’t happen by accident. It is the result of years of careful work by the scientists at the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (CSIR-NEERI). They created a special method called Eco-Rejuvenation Technology (ERT)—a simple but powerful process to bring life back to damaged and polluted land.

The idea was not just to plant trees, but to heal the soil first. The team treated the land with natural materials to improve its quality, planted native trees that could survive in tough conditions, and slowly built a green cover that could stand strong even in dry weather.

The purpose was clear: to show that land polluted by fly ash from power plants doesn’t have to stay dead. It can be brought back to life with the right care, science, and patience.

The Better India spoke to Dr Lal Singh, Principal Scientist and Project Leader at CSIR-NEERI, who shared how this method is now giving hope to many more places across the country that are struggling with polluted land.

From wastelands to farmlands: How one scientist sparked a powerful green revolution

What began as a simple assignment soon became a life’s mission for Dr Lal Singh. When he first joined CSIR in 2006, he was only trying to prove himself to his seniors. But what followed changed the course of his career—and the lives of thousands.

“I was assigned to convert a uranium tailing pond in Jharkhand back in 2006. That’s when I joined CSIR. We adopted the bamboo plantation method to eradicate the water and land pollution in the site, and it worked. This was my first project, and there was no looking back,” Singh shares with The Better India.

The success of this first attempt planted a seed in him—if a dead, polluted pond could be revived, what else could be brought back to life?

Step by step, project by project, Dr Singh and his team proved that barren, damaged lands could be saved.

Step by step, project by project, Dr Singh and his team proved that barren, damaged lands could be saved.

In 2013, Dr Singh faced a bigger challenge. He was asked to convert degraded, fly ash-laden land near Nagpur in Maharashtra into something useful for farming. “This was my first project in the state. I was given Ubagi and Khapari villages in Maharashtra. They are 24 kms away from Nagpur. I worked on a 10-hectare polluted wasteland and in two years it was rejuvenated and in four years it was ready for crop cultivation,” he says.

Step by step, project by project, Dr Singh and his team proved that barren, damaged lands could be saved. This was no quick fix—it took years of planting, soil care, and patient observation. But each patch of green made it possible for local farmers to return, grow food, and build healthier lives.

What started as a technical experiment has quietly grown into a movement—a green revolution that not only cleans the land but also restores livelihoods. For Dr Singh, this work is no longer just a job. It’s a mission to make sure that polluted, forgotten places can be turned into homes for trees, crops, and people once again.

Fly ash, forgotten lands, and the villages that paid the price

For years, the villages near the thermal power plants in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha district lived under a cloud—quite literally. Fly ash from the power plants settled on their crops, filled their air, and polluted their water. The land, once rich and alive, slowly turned into a dumping ground.

“It’s been seven years since the people belonging to adjacent villages forgot about the fly ash problem, the air, soil, and water pollution it caused. All thanks to the eco rejuvenation project,” says Dr Lal Singh in conversation with the Better India.

Fly ash, a fine powdery waste released from burning coal, was dumped into low-lying areas near the power plants. These tailing ponds became large pits of toxic waste. Over time, the ash didn’t just stay in the ponds—it blew over the fields, settled on crops, mixed into the water, and filled the air people breathed.

“Due to the fly ash problem, farmers’ productivity was reduced drastically as the fly ash settled on their crops. Women had no livelihood, and everyone in the nearby villages breathed bad air. The team decided to eradicate all the problems and began to rejuvenate dump sites,” Dr Lal Singh explains, his voice carrying the weight of what these villages had suffered.

The damage was not just to the land—it affected entire communities. Crops failed, incomes dried up, and clean air became a luxury. But turning things around wasn’t simple.

“Clearing the lands for bamboo cultivation was the biggest challenge of all,” Dr Singh shares. The soil was weak, the waste was thick, and preparing the ground for new life demanded relentless effort.

Yet, despite these obstacles, Dr Singh and his team pushed forward—step by step, tree by tree—showing that even the most forgotten lands could be brought back to life.

How rejuvenated lands brought new life to farmers and women

For years, farmers in these villages struggled to grow their crops. The fly ash from nearby power plants settled on their fields, coating pulses, cotton, and soya with a fine layer of dust. Their harvests shrank, their incomes disappeared, and their hope slowly faded.

For years, people believed these areas around Koradi, Khaparkheda, and Chandrapur Thermal Power Stations were beyond saving.

For years, people believed these areas around Koradi, Khaparkheda, and Chandrapur Thermal Power Stations were beyond saving.

“The fly ash has a component called ‘silica’ which usually settles on the crops. This cut down the productivity of the crops. Bamboo is a plant that attracts silica, and this helps in making sure crops are not affected as the bamboo sites attract most of the silica in the air,” explains Dr Lal Singh, sharing the simple but powerful science behind the solution.

By planting bamboo, they weren’t just adding greenery—they were creating a natural shield, a silent protector that would pull silica out of the air and away from the crops. Slowly, the air grew cleaner, the soil stronger, and the village lives began to shift.

“It’s been seven years since we have had this green belt and we are fortunate to breathe clean air today,” says Pranali Sahara, a resident of Koradi Nahadula, a village just 10 km from the dump site. Pranali, a single mother of two, never imagined this dead land could become a place of work and pride.

“I have worked here for the last seven years. We never thought this place would transform like this. Today we have clean air, water, and healthy soil. I am the only one who earns in my family, and I also got a job because of this project,” she shares with a smile that carries both gratitude and quiet strength. Pranali now earns Rs 5000 a month tending to the bamboo plantation, caring for the site that has, in many ways, cared for her in return.

Dr Singh adds, “From cleaning the land to watering the bamboo trees and taking care of the site, we have 20 women employed. All these women are employed on a three-year contract.”

The Eco-Rejuvenation Technology is an eco-friendly, cost-effective solution developed by CSIR-NEERI (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research – National Environmental Engineering Research Institute).

The Eco-Rejuvenation Technology is an eco-friendly, cost-effective solution developed by CSIR-NEERI (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research – National Environmental Engineering Research Institute).

Among them is Geeta Chauhan, another mother from the same village. With two children depending on her, Geeta says the opportunity came when she needed it most. “It has been six years since I have worked at the site, and this job was created because of this project. I can earn and support my family now. We also feel blessed to breathe clean air and drink water that is not polluted,” she says.

For women like Pranali and Geeta, this project is more than just a green belt. It’s a lifeline—a place that gave them back their dignity, their health, and their ability to provide for their families.

What once was written off as useless land is now a living, breathing space where women work, crops grow, and children play in the fresh air—proof that when science and community come together, even the most broken places can bloom again.

The Eco-Rejuvenation Technology is an eco-friendly, cost-effective solution developed by CSIR-NEERI (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research – National Environmental Engineering Research Institute). It was designed to restore and rejuvenate degraded or contaminated lands, particularly those affected by fly ash, heavy metals, or industrial waste.

Dr Singh says, “From cleaning the land to watering the bamboo trees and taking care of the site, we have 20 women employed. All these women are employed on a three-year contract.”

Dr Singh says, “From cleaning the land to watering the bamboo trees and taking care of the site, we have 20 women employed. All these women are employed on a three-year contract.”

Dr Lal Singh explains that there are five parameters before adopting the ERT to rejuvenate degraded land. According to the scientist:

- Selection of the degraded area with the source of contaminants.

- Screening and selection of tolerant plant species.

- Application of desired microbial inoculants.

- Amendment with organic substances, and

- Application of desired fungal inoculants.

“After these parameters are accessed, we pick the bamboo sapling to be cultivated on the contaminated land,” adds Dr Singh.

Stating that selecting the bamboo sapling is a crucial process, Dr Singh says that picking a species of bamboo that consumes less water is important, as most parts of Maharashtra face water scarcity. “I usually select a plant that is cost-friendly and has a high leaf persistence value. A leaf with a high leaf persistence value doesn’t wither away easily. The sapling should also be fast-growing and mitigate dust,” the scientist adds.

Taking the green revolution beyond Maharashtra

After breathing life back into the dusty lands of Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region, Dr Lal Singh and his team are not stopping. The success here has become a starting point—a blueprint for healing broken lands across India.

Their next mission takes them to Odisha, where the land tells a different story of damage. “A site in Odisha, which is polluted because of phosphorus ore, is our next target. We plan to implement ERT with bamboo saplings,” Dr Singh shares.

Their next mission takes them to Odisha, where the land tells a different story of damage.

Their next mission takes them to Odisha, where the land tells a different story of damage.

The challenge in Odisha is just as urgent. Phosphorus ore has left behind poisoned soil and damaged ecosystems. But Dr Singh’s team is hopeful that the same bamboo-led solution, which worked wonders in Maharashtra, can bring fresh air and green life to this forgotten space.

And they’re already looking further. In Uttar Pradesh’s Antara, the team has identified another area in trouble—one where fly ash is now threatening not just the land, but a nearby water reservoir that local communities rely on.

“After Odisha, our team will work on lands in Uttar Pradesh’s Antara, which is under the fly ash threat and is affecting a water reservoir. We plan to develop a green belt around Antara to protect the reservoir and prevent water pollution,” he adds.

This is not just about cleaning up pollution—it’s about protecting water, rebuilding land, and creating safe spaces for families and farmers who live around these contaminated areas. Dr Singh’s vision now stretches far beyond Maharashtra, carrying the hope that what worked here can inspire change across the country.

Each project is a step towards proving a simple but powerful idea: no land is beyond saving.

Edited by Leila Badyari; All images courtesy: Dr Lal Singh

News