From Shaheen Bagh to ‘Uprooted’, an ‘uncomic’ journey of speaking out

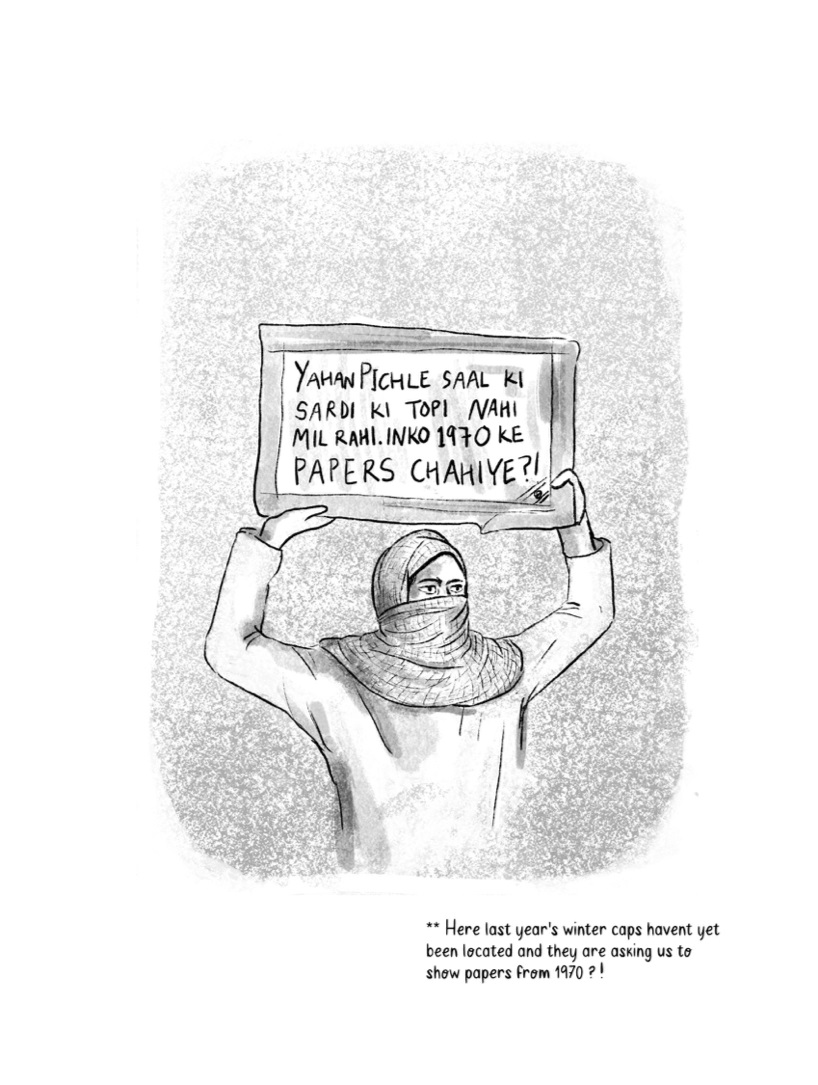

Spending months at the Shaheen Bagh protest site, she captured more than what met the eye — seamlessly going beyond the visual of hundreds of burqa-clad women sitting in protest. There were anecdotes from their lives, moments beyond the agitation, humour, the never-ending Kafkaesque trials, small hopes, and the tiny details of a big revolution in the making. Perhaps that is what made ’Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection’ (Yoda Press) so alive, no, human.

In her latest, ’Uprooted’ (Westland), Mehrotra enters the forest — both physical and metaphorical. The ‘method writer’, who has long been interested in the ongoing forest rights struggles, spent months living with the Van Gujjar community — not with a project in mind. Much like her previous work, ‘Uprooted’ grew from notes, conversations, observations and drawings from her time in these areas, as well as her other work on forest rights, women’s rights and education.

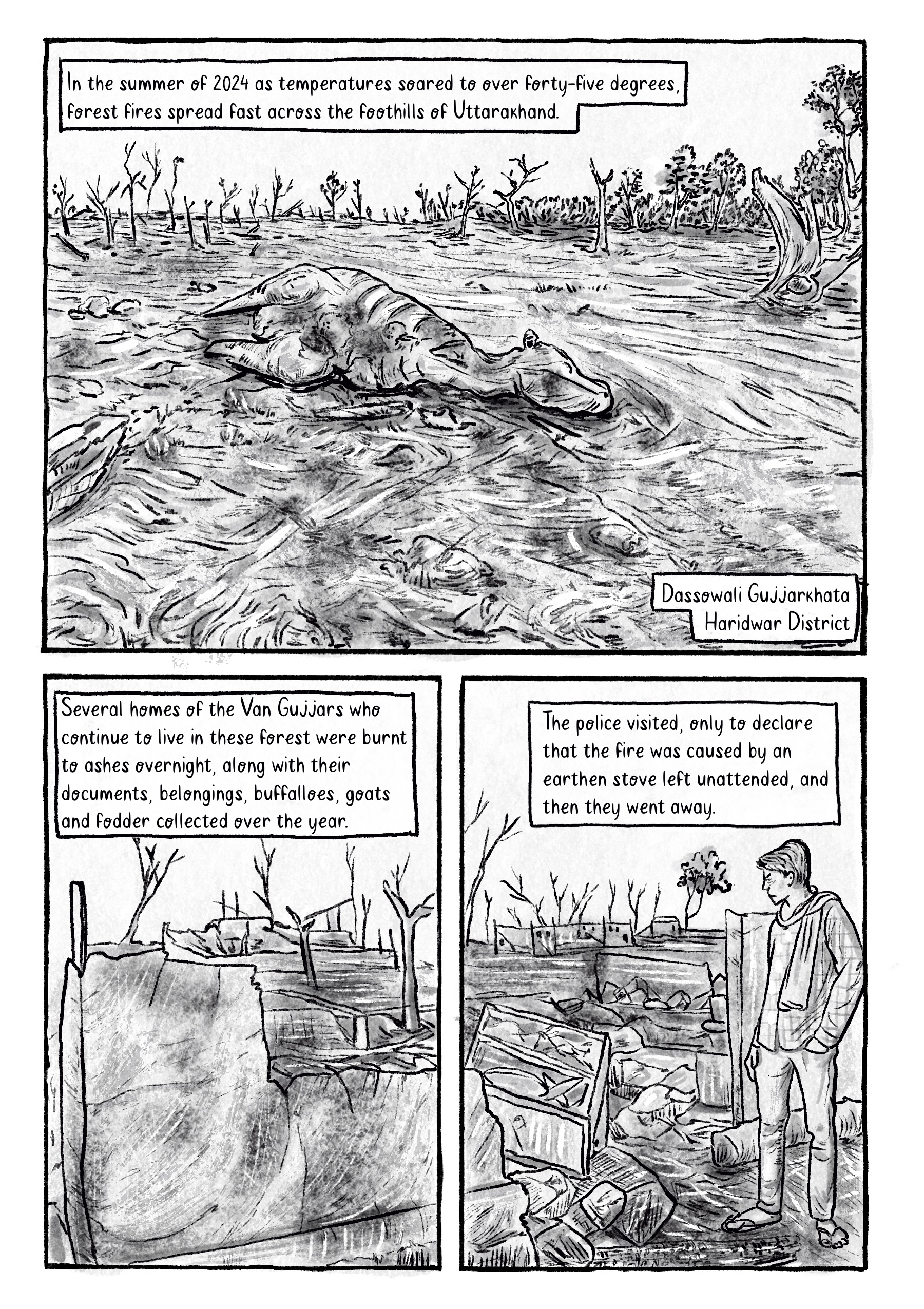

From ‘Uprooted’

From ‘Uprooted’

“There had been a lot of news about the extractivism of natural resources — forests and coastlines being bought up by big corporations. For me, it is important to hear directly from people waging struggles against these forces on the ground — for their own livelihoods and rights, and for ecology itself,” she says.

While displacement — both mental and physical — permeates her work, the process of creating ‘Uprooted’ involved moving through forests, following women on grazing routes, travelling across resettlement sites and highways under construction and tracing migratory paths uphill during summer.

Though the Van Gujjar community is traditionally semi-nomadic, moving between forests and higher mountains in summer, they have increasingly been labelled encroachers and pushed away from their traditional buffalo-herding work toward more settled agrarian labour — or, often, left without resettlement at all.

“The resettlement locations are cleared of forests, and the tiny agricultural plots do not meet the needs of families moving there. There are many layers of this forced and structural dislocation — it is ultimately meant to control people. In this case, they (the Van Gujjars), being a Muslim community, are also facing the brunt of increasingly Hindutva governance and vigilante groups in Uttarakhand,” Mehrotra adds.

The author began her journey by visiting deras within the forests near Dehradun with a lawyer friend, and then slowly ventured to other areas where the Van Gujjars continue to live inside what is now Rajaji National Park, despite ongoing threats from the Forest Department.

“My conversations with leaders and community members were always woven into daily life — while working with buffaloes, cooking, mending houses, taking cattle for grazing. It was only after the day’s work that the women had time to talk, so it was important for me to stay there overnight when I could, or into the late evenings. Though these forests are no longer far from highways and towns, they still feel like a parallel world — ensconced between old trees, surrounded by Gojri buffaloes, drinking endless cups of milk tea, with no phone signal or urban amenities. Life there is difficult and requires immense skill — the communities know the wild animals and the local ecology so intimately. Similarly, in the resettlement areas, I made friends with young women leaders like Aamna and Teena, who have been teaching and reviving their Gojri crafts,” she recalls.

Uprooted by Ita Mehrotra. Westland. Pages 144. Rs 599

Uprooted by Ita Mehrotra. Westland. Pages 144. Rs 599

Mehrotra maintains that she has not tried to strike a balance between the political and the personal in her latest work: “It is all affective and conversational, where the personal and political are continuously intertwined. The book is rooted in people I have come to know well and continue to work with on educational projects.”

She stresses that each book is a long, evolving journey. “I grow with it — both in my skills and in my experiments with the medium — trying to find new ways to bring image and word together, and to research and collaborate with communities. I am also continuously questioning the ethics of producing books in English, which are hard to access in these spaces, and exploring other formats of publication.”

She believes that a work like ‘Uprooted’ does not attempt to “answer” questions or offer quick solutions but seeks to connect the dots between various aspects — historical anti-people forest policies, conservation laws that further disenfranchise, state violence, and grassroots organisational work. “Graphic narratives can leave enough room for readers to think and form their own questions and associations. I believe leaders, educators, and activists across communities are really the ones to listen to, support, and work alongside. The book is political—and invites readers to dig deeper,” she adds.

Reflecting on her previous work, Mehrotra insists that Shaheen Bagh is still a strong memory — and will continue to do so — for anyone who was part of the protests. “When I was making that book, it was so soon after the protests and it was really a way to keep that fire alight. I now feel it’s important to continue that narrative, especially considering the Delhi riots case and what Umar Khalid, Gulfisha and others are enduring.”

From ‘Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection’ by Ita Mehrotra.

From ‘Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection’ by Ita Mehrotra.

While ‘Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection’ documented a particular time, moment, and landmark movement in history, ’Uprooted’, she says, is an ongoing process — one she hopes can become part of continuing struggles in some way.

“It’s been interesting to see how the pages can be repurposed back in the organisations — as posters, pamphlets, and other material. And yes, I do think my work is about talking, drawing and documenting a kind of memory-keeping and history that mainstream media and the powers that be would rather erase and silence.”

Ask her whether, in the current social and political climate, graphic novels can still serve as a means of resistance, and she asserts that amid today’s inundation of information, a key strength of the graphic narrative is that it leaves space — empty moments between images and words — for the reader to think, pause and associate. “The viewer has to be in the frame and is implicated by the story. In that sense, it pushes against the tide,” concludes Mehrotra, who is inspired by political comics makers on social media like ’Sanitary Panels’ and the work of Orijit Sen and Vidyun Sabhaney, who have recently documented right-to-food issues in India.

— The writer is a freelance contributor based in Chandigarh

Book Review