Flying colours

“When we woke up late in the afternoon, we went up to inspect the world from the roof of our tall house. We were staggered. Not by the grand vistas of lofty but higgledy-piggledy civic architecture before us, but what was above us. The deep blue yonder was awash with hundreds of multi-coloured little shapes! What I beheld on our first day in Lahore was a sensational tournament of flying colours. It was a dance in the sky of a dizzying display. And its impression made on me that day was everlasting.”

— Balraj Khanna in ‘Born in India, Made in England: Autobiography of an Artist’ (Unicorn Press)

That sky was to become his canvas for life. And those shapes, the kites, and the idea of flight were to fuel his art over the next eight decades. Free-flowing figures swayed his canvases — breezy, meditative, contemplative. The swirly gatta sweet, toys, puppets, festivals, magicians, jugglers, sword swallowers, fire eaters — all ubiquitous motifs from his childhood — would appear and re-appear in his art, firming his place in the pantheon of art in the United Kingdom, where he lived and died a celebrated artist and writer in January last year. The Tate UK’s acquisition of three of his major works and an exhibition at the Tate gallery recognise his ability to bridge eastern and western artistic traditions.

The late Balraj Khanna’s art is a fusion of his Indian heritage and roots and his life in the UK.

The late Balraj Khanna’s art is a fusion of his Indian heritage and roots and his life in the UK.

Born in Jhang in 1939, he lived in Lahore, Qadian, Karnal, Shimla, Nangal, Chandigarh, wherever his father, an electrical engineer, was posted. He was in Qadian when the Partition took place, escaping death by a whisker — in actual, it was forceful sunnat done by some hooligans. All those memories impacted him for a lifetime, manifesting as the novels ‘Nation of Fools’ in 1984 and ‘Line of Blood’ in 2017.

Khanna had been painting often when he was in college, but took to it passionately when pursuing MA in English at Panjab University. “…I had been painting furiously, experimenting with light and shadows and trying to evolve my own kind of abstraction,” he notes in his autobiography. It was during these days that art critic and novelist Mulk Raj Anand visited PU. He happened to see Khanna’s works in his friend’s room and wished to meet him. That same year, Khanna was to leave for the UK to pursue further studies in English literature at Oxford University, but things were to pan out very differently.

Nairobi Nights.

Nairobi Nights.

Anand had given him five letters of reference, but told Khanna it would require more than talent to survive in the UK. It would demand dedication, and not just through the harsh weather. In November 1962, he landed in England — and it was exactly as Anand had described: racist, prejudiced, indifferent. No Negroes. No Indians. No Irish — notices made it loud and clear. Thankfully for Khanna, he already had a former teacher from college there to help him out. And there were those five introductions.

These letters were addressed to artists FN Souza and Avinash Chandra, poet Dom Moraes, George Butcher, the then art critic of The Guardian, and WG Archer, Indian art expert and Keeper Emeritus of the Indian Section at the Victoria & Albert Museum. The latter was to give him his first solo show at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum in 1968. Along with Chandra, Khanna would go on to showcase his work at the seminal, and controversial, exhibition of Asian, African and Caribbean artists in post-war Britain, ‘The Other Story’ (1989) at the Hayward Gallery in London.

Meanwhile, he fell in love and married Frenchwoman Francine, with whom he had two daughters — Kaushaliya, an architect and artist, and Rani, a filmmaker and doula. It was in Metz, his wife’s hometown in northeastern France, that he was to truly emerge as an artist. He had been forced out of action following a catastrophic accident in 1965. While recovering in the French countryside, he found himself close to nature and once on his feet, he began to see things differently. On his canvas, it changed his expression from semi-figurative and semi-abstract to a new kind of abstraction. He was making his own canvases, a craft he had learnt from Souza, and illuminating them with swirls big and small, geometric shapes and those imbibed from nature. He credited this time with instilling ‘a new force’ in his practice, inspiring his multi-layered abstract works. Incorporating organic and geometric forms, Khanna sought to express what he called ‘the theatre of the natural world’. This, incidentally, is also the title of his show at Tate, which is on till July 6. Last autumn, Jhaveri Contemporary had presented a suite of paintings by Balraj Khanna from this very period at the Frieze Masters.

Haldighat Petite.

Haldighat Petite.

Today, his works are accessible in public collections all over the UK and in the National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, and PU. Top British critics have hailed his paintings, created over finely textured canvases of sand and primer. They have often compared him to Paul Klee and Joan Miro. In a 1990 catalogue essay, the late curator Bryan Robertson wrote: “…Nobody in England is painting like Khanna. The delicate gravity and slow-moving, warm effulgence of his paintings with their complex layers of surface reflect the attributes of a world that is utterly Khanna’s own. Is it an Indian world? I don’t think so…” Tate’s curator Carol Jacobi praised the immersive quality, essential emotional aspect and strong intellectual base of his artworks. Some of these include ‘Dawn’ (1980), evoking the stillness of an early spring morning; ‘Birth of a Body’ (1977), symbolising new life; ‘Two Lovers’ (1978), exploring intimacy and connection; and ‘Birth of a Nation — Bangladesh’ (1971-72), on the creation of Bangladesh.

Distinguished art historian and critic Richard Cork, who was on the committee that supported ‘The Other Story’, has closely followed Khanna’s career trajectory. For him, his 1987 exhibition at London’s Horizon Gallery marked an outstanding moment in his career. “Concentrating on work executed since 1985, it was filled with paintings of forms he delighted in unleashing. They were allowed to proliferate in this exhibition, moving through his canvases with untrammelled ease and a liberating sense of spaciousness,” he shares.

In A Flux.

In A Flux.

The 1980s were a defining period for the artist. As Cork says, it enabled him to “establish himself as an artist who had arrived at a full definition of his own creative identity”. He believes Khanna was a marvellously resolute artist who refused to feel downhearted about the racist prejudice he encountered in the UK. “Although the Tate never gave his work an exhibition while he was alive, Khanna remained an essentially optimistic individual who believed in the viability of his own vision,” Cork adds.

And a week before his death, Khanna had called Ishrat Kanga, his friend and Director, Specialist and Co-Worldwide Head, Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art at Sotheby’s, to tell her about the upcoming show and acquisition of his works by the Tate (which houses the UK’s national collection of international modern and contemporary art). “He felt he was finally getting the recognition that he hadn’t gotten so far in his life. He was so excited to be acquired by such a major institution and to have a display,” Kanga recalls.

This acquisition and display of Khanna’s works is important as it recognises what art historian Alice Correia calls “long-standing, structural, institutionalised racism and neglect by Britain’s art historians, curators, and galleries”. In the article ‘Absence in Post-War British Painting: South Asian Modernists in Regional Collections’, she quotes Khanna as writing in 1981 on the nature of Britain’s white art world: “Hypocrisy, superciliousness, vanity and arrogance are some of its traits, mainly located in the cliques that control art journalism, exposure, sponsorship and general patronage. Arguably it is tough for any artist at the best of times, but for some reason it is tougher even for artists as good, say, as Avinash Chandra, Francis Souza and Rasheed Araeen; the lesser ones do not stand a chance. Some may say this is a kind of racial discrimination and they won’t be wrong if they do.” So how did Khanna do it? Well, perhaps because he was, as Mulk Raj Anand had called him, “a Punjabi ziddi nut”.

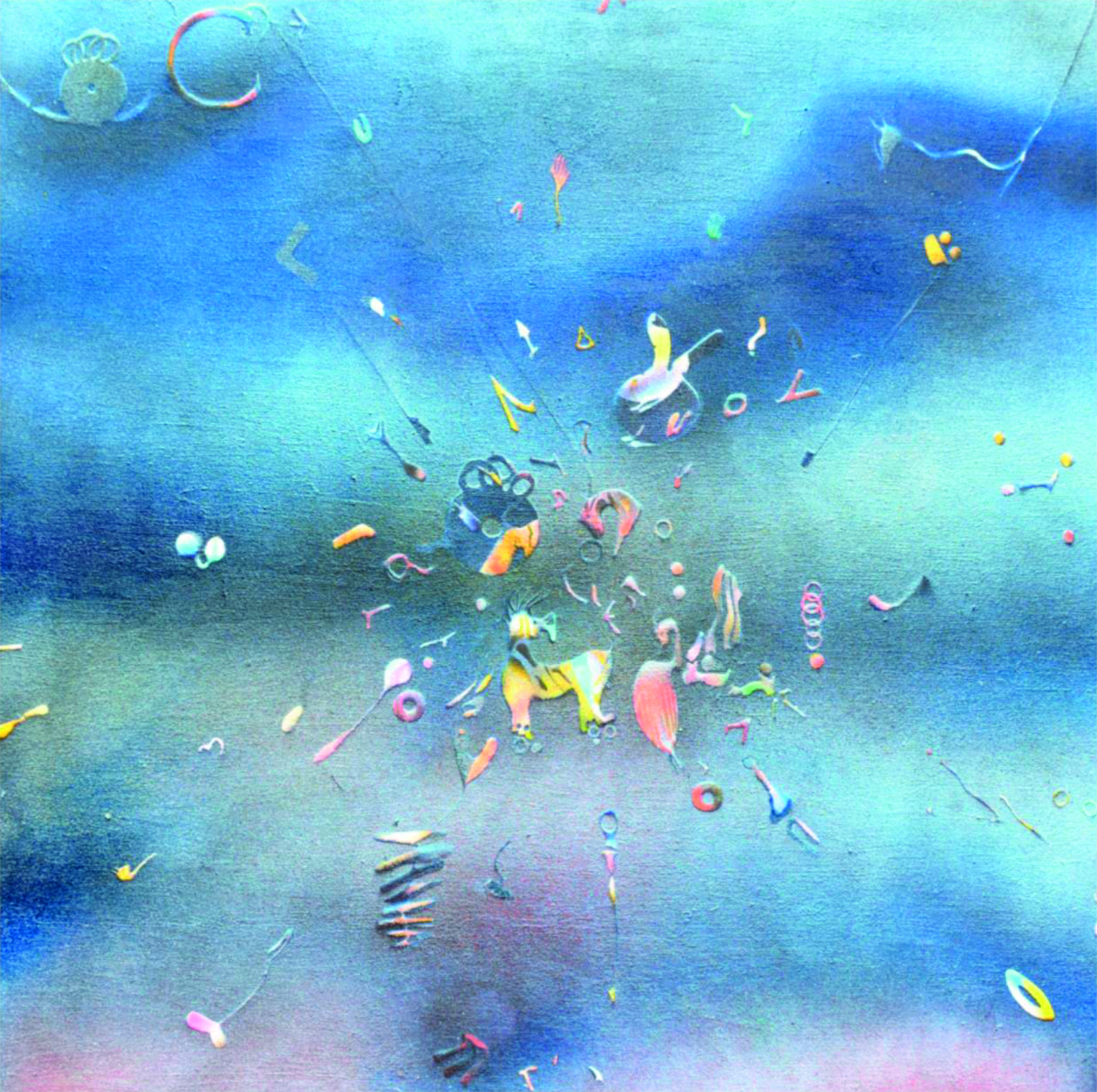

Playful Forms.

Playful Forms.

Khanna’s writing had an unfailing idiom of expressing Punjabiness in English. His art wasn’t any different. Kanga says his work was a wonderful fusion of his Indian heritage and roots and his life in the UK. “Though abstract on the surface, he always titled them using his childhood memories (‘Mela’, ‘Jadugar’, et al). Even the colours are always referencing where he was born and his homeland. It’s a nice mix of his culture, his roots, his heritage, and then also his new adopted country. That’s what makes his work so special and I think that’s why he appeals to a very diverse population.”

Cork’s favourite is ‘Patang Bazi’ (1987). He calls it a “particularly loveable painting”. It refers “to the kite matches Khanna recalled playing with relish during his childhood in the Punjab. The forms hovering on the surface of this canvas are reminiscent of the coloured paper structures which Indian children still make for this fiercely competitive yet exhilarating sport. One of Khanna’s most dramatic achievements is an enormous 1986 painting called ‘Coming from Edinburgh’. Ostensibly concerned with celebrating a visit to Scotland’s capital city, the composition takes on an infectiously festive air, tumbling and spiralling with a spirited energy redolent above all of the circus,” says Cork. This energy was infectious. As Khanna would say, “An artist must delight himself before he can expect to delight anyone else.”

For someone who was dedicated to his roots all his life, his death last year went unnoticed in his birthplace. However, his tenacious flight of fantasy has opened the gates hitherto closed for non-white artists, unleashing the kites in brand new horizons. And that matters.

Subah Saveray.

Subah Saveray.

The writer painter

Equally gifted as a writer, Balraj Khanna’s 1984 book ‘Nation of Fools’, set entirely in Chandigarh of the 1950s, won The Winifred Holtby Prize, awarded by the Royal Society of Literature. In 1999, it was adjudged ‘One of The Best 200 Novels in English Since 1950’ by The Modern Library. His autobiography, published in 2021, is a vibrant account of India of the times and that of a migrant trying to find his feet in the UK. His last was ‘Line of Blood’, based on Partition. Khanna’s writing is intense, funny and heartfelt. Like his painting, it comes from the heart. In a 2017 interview, he had told The Tribune how he would laugh out loud while writing ‘Nation of Fools’. “Things I had never thought of before suddenly invaded my consciousness — memories long dormant of the behaviour of people I had known and situations. I cried copiously while writing ‘Line of Blood’, a work of total fiction grounded in what I witnessed aged 6/7 circa 1947, a brutal period in world history, India’s Holocaust.”

Features